Environmental psychology is a study of how we, as individuals and as part of a group, interact with physical conditions. Experience and change the environment and discover how the environment changes our behaviour and experiences. In environmental psychology, “environment” includes natural and man-made objects, namely, natural resources, parks, houses, From workplaces, public spaces, private scales to rooms, buildings, neighbourhoods, cities, wildlife, and global scales.

Environmental Psychology, also known as architecture psychology, is a relatively new field, about 50 years old, and has developed rapidly in response to the deterioration of environmental health and the need to design buildings to better reflect the needs of the population. One of its main goals is to understand the environment and people’s trade and use that knowledge to influence policies that promote sustainable action and help create a more liveable and greener built environment.

Origin

Environmental psychology was a new branch of psychology that developed in the late 1950s and 1960s. It is mainly about the interface between human behaviour and the socio-physical environment. It can be defined as the study of the trades between people and their physical conditions while people change their environment and their behaviour and experiences are also changed by the environment. Environmental psychology includes theory, research, and practical application aimed at improving relationships with the natural and built environment.

The first theoretical approaches relate to the psychology of cognition, which have been developed from more ecologically oriented perspectives, such as Brunswick’s “Lens Model”, Princeton Group’s Transaction School, and Gibson’s “Ecological Approach” to cognition. It has more to do with a “molecular” approach to the spatial-physical environment. He paid more attention to the individual sensory-perceptual features of the environment that directly interact with our senses.

The second approach builds on the social psychology approach developed through the work of authors such as Levin, Tolman, Barker, and Bronfenbrenner. The second approach takes a more “holistic” or “molar” approach that evolved into a transaction-contextual approach to human-environment relationships. This approach is still considered a major theoretical perspective in environmental psychology.

Environmental psychology, as a branch of academic psychology, is often attributed to the Proshansky group at the City University of New York, which has been studying human-place transactions since 1958. Ward placement in hospitals will be both useful and harmful to patients. Realizing that there are not many answers in their respective fields, a new study was needed, so they actually started to establish a new study.

Career options in Environmental Psychology

Another important point of EP is the impact of urban and natural environments on people. More and more environmental psychologists specialize in the recovery environment, a place that helps people recover from their daily mental overload. For example, walking in nature reduces stress, improves alertness, and reduces anger. This study shows the importance of protecting accessible green spaces, affecting the structure of cities and homes.

Place Attachment

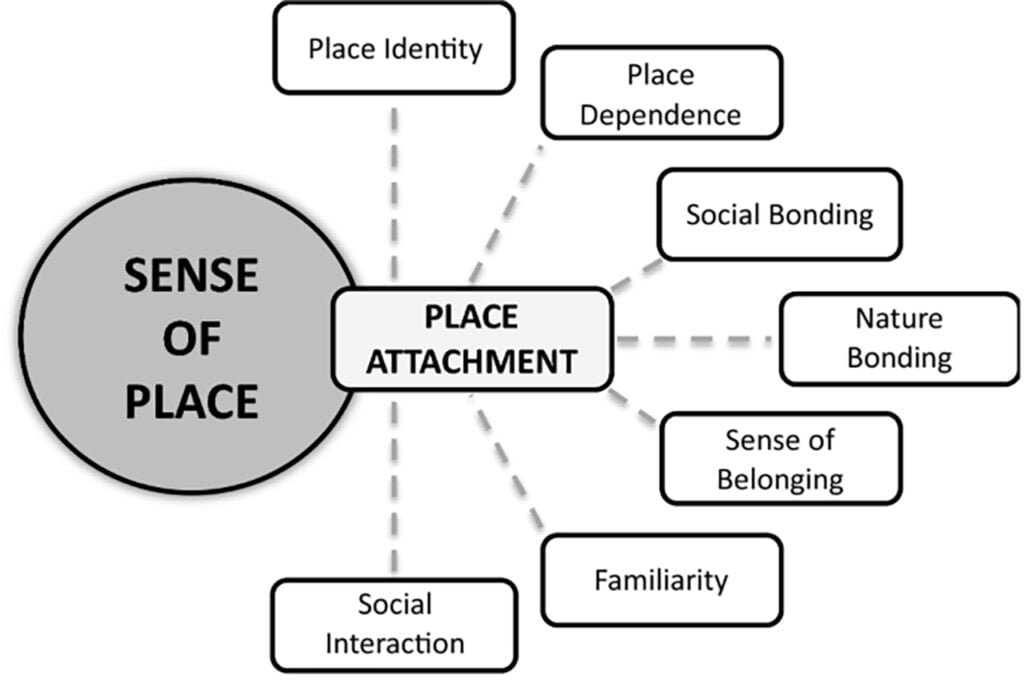

Place attachment is the bond between people and places. It is a complex interrelationship of cognition, emotion and behaviour. With the rise of globalization and mobility, place attachment has become of particular interest, as person-place bonds have become increasingly tenuous. This, in turn, can affect the perceived safety and comfort of the environment and cause people to weaken the protection of those places. For this reason, and because attachment to a place is also associated with awareness of environmental risks, attachment to a place is very important for understanding environmental protection behaviour.

Place attachment is highly relevant for understanding public acceptability of renewable energy developments, such as wind parks and hydro-energy projects. Place attachment is also relevant for disaster psychology and have been used to understand and alleviate the grief of those displaced.

Wayfinding

There are diverse applications for people to know how to find their way in the built natural environment. For example, psychologists used this study to catch criminals and find people lost in the wild. It was also used to find ways to evacuate dangerous areas faster, such as burning hotels and smoke-filled train tunnels. Pathfinding research has also contributed to the development of a head-mounted display that helps firefighters navigate in an emergency.

Architecture and Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology helps us understand the practical application of concepts such as spatial perception and cognitive mapping to navigable design spaces. Good signage inside buildings speeds up movement inside buildings, color-coded routes reduce navigation errors in buildings, and simplified maps for bus and train routes make cartographically accurate routes Easier to navigate than in the city. A striking landmark for improving spatial knowledge such as cities is the result of environmental psychology research.

Environmental psychology was the first to make a name for itself in the world of architecture. For decades, environmental psychologists have been working to improve buildings by: Focusing on the Human Factor in Building Design. Environmental Psychologist Asks the following questions: How People Navigate in Buildings What do users of Building need and want in a building? How can I apply this knowledge to modern architecture? The answers to of these questions include more than shipping hospitals, classrooms that enhance learning and participation, and to reduce complaints about the ‘s built-in settings.

Syllabus

The field of environmental psychology takes an interdisciplinary approach to the study of people in the physical context, with elements of social sciences (psychology, geography, anthropology, sociology) and design fields (landscaping, architecture, city planning). Put together to provide a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics between people and their physical environment.

Main objectives

- To introduce the origins, basic theories, methods, research and applications in the field of environmental psychology.

- To develop an appreciation of how psychology can contribute to shaping urban environments, preserve natural environments, and deal with the challenges of environmental and climate change.

- To develop students’ capacities to be able to perform a basic research, practice or policy work in the field of environmental psychology.

Course Contents

Environmental Psychology: History and Scope

Define the field of environmental psychology. Origin and history. Environmental Psychology is associated with other disciplines. An important theoretical perspective in environmental psychology. Complexity, change with hours. The impact of the environment on human cognition and behaviour. Location-based theory of environmental psychology.

Overview of the Research Methods in Environmental Psychology

The main principles behind the use of research methods in environmental psychology. A variety of methods are immediately available, including observations, behaviour mapping, GIS, surveys, interviews, and diaries. Mixed method study. Laboratory experiments and natural experiments. evaluation. Action research. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Data analysis in environmental psychology.

Urban Environments: Overcoming Stressors with Opportunities

Urban stress. Environmental overload theory and attention recovery. Crime and rudeness in the urban environment of Housing, health and welfare. Culture and urban environment. City as a space of cohabitation, culture and reconstruction.

Environmental Psychology’s Role in Designing Spaces

Environment and quality of life. Participatory design. Design a sustainable city. Crime prevention by environmental design. Designing an educational environment and an environment for children. Designing a healthy environment.

People and the Nature

The inner connection between people and nature. Recreational ability in a natural environment. Anthropocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric worldviews. A new environmental paradigm. Connection with nature. Environmental changes: Impact on human health and well-being. Conservation psychology.

Environmental Risks and Interventions

Natural disasters and ecological threats: environmental risk and risk awareness, cognitive and the role of emotions, human behaviour in the face of risk, risk awareness and resilience. Interference with the habitat of people: acceptance and NIMBYism; find the right balance for the public good.

The Psychology of Pro-Environmental Action

Environment and climate change: An urgent agenda. Psychological drivers of environmental protection behaviour: the role of environmental attitudes, social expressions, norms, beliefs, values, identities, environmental knowledge, and direct experience. A model for explaining environmental behaviour. The role of customs and social practices. Ripple of action: myth or possibility? Promotion of environmental behaviour through intervention. The role of environmental education. Environmentally friendly behaviour in organizations.

Conclusions: Building links between Science, Policy and Practice

How can environmental psychologists work well with policies and practices? Use of research results to inform policies and practices. The role of evaluation research. Conduct to spread the study of environmental psychological effects. The role of Environmental Psychology in facilitating collaboration between different sectors.

Universities

A growing number of universities offer formal or informal graduate programs in psychology departments, schools of architecture, and other departments. The following are some of the top EP programs around the world.

City University of New York

This five-year PhD program collaborates closely with the social/personality psychology program and the human geography program. The program’s goal is to increase practical knowledge that will lead to a more just and sustainable environment.

University of Surrey (UK)

The University of Surrey offers an MSc graduate program. It is one year long, consisting of eight classes and a dissertation. The aim of the program is to provide students with both theoretical and practical knowledge of EP. It emphasizes research that has practical benefits for policy and planning.

Colorado State University (USA)

The Applied Social and Health Psychology MA and PhD programs at CSU offer a concentration in EP. Students learn methodologies and techniques for investigating such topics as managing natural resources, promoting sustainable behaviour, and designing learning environments. The program is flexible, and students can take on seminars and research projects that work towards individual career goals.

University of Victoria (Canada)

UVic Psychology graduate students have the option of entering the Individualized Program in EP. Coursework is determined by the broad environmental psychology interests of students in consultation with their supervisor, Dr. Robert Gifford.

Humboldt State University (USA)

Humboldt offers a two-year MA program in Social and Environmental Psychology. Students study human environment interactions, environmental issues, and how to positively influence others towards addressing environmental concerns. Successful graduates are prepared for work in organizations that are concerned with the environment, and may also pursue PhD studies.

University of Groningen (the Netherlands)

The one-year Masters EP program at the University of Groningen focuses on the human dimension of environmental and energy problems. Students follow theoretical and methodological courses and write an individual thesis, with possibilities to join ongoing collaborations with practitioners, governments, knowledge institutes, and scholars from other disciplines.

Scope of work

Environmental psychology focuses primarily on optimizing and enhancing the human environment by improving the work of design professionals such as architects and city planners. It has to do with maintaining a balance between people and the environment. This includes research on urbanization, urban planning, the scream effect, improving slum environments, improving work and office spaces, and living conditions. Another important aspect that expands the scope of environmental psychology is ergonomics, the scientific study of designing objects and spaces. It is optimal for human use.

In addition, in recent years, dealing with environmental problems such as pollution, climate change, and deforestation has become more important. Environmental psychology also aims to change behaviour in ways that benefit the environment and address these environmental challenges, as well as ensure quality of life and human well-being. This leads to the concept of sustainability, an important principle in environmental psychology. Today, it is a major field of environmental psychology.

Therefore, environmental psychology has broad application in both man-made and natural environments. It covers a variety of topics such as urban planning, architecture, interior design, and behaviour modification for sustainable practices. This is a fairly new field with a lot of room for growth and interaction with other disciplines. The ever-changing environment demands new and more up-to-date research in the field of environmental psychology.

Organizations

This is the global-level home of environmental psychologists. It is part of the International Association of Applied Psychology. The goal of Lesson 4 is to study the interactions between people and their physical environment and use this knowledge to improve our physical parameters. Division 4 invests in knowledge of buildings, parks, and the atmosphere and works to reduce poverty, crime, climate change and other negative aspects of the built environment.

Founded in 1981 in Europe, IAPS is the now the home of environmental psychologists from about 40 countries. The primary goal of IAPS members is to improve the quality of life through a shared concern for people and their interactions with the environment. They do this through Research Collaboration as well as Policy Changes through lobbying efforts.

- Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA)

EDRA is a large association of environmental psychologists and others who study and advocate for environments that improve the quality of life. EDRA’s function is to advance research that benefits both the built and natural environments, and it has been doing so since 1968.

Environmental Psychology and the world

One of the key challenges that EP can help address is the application of psychological knowledge to protect the natural environment. Addressing human behaviour is paramount to protecting nature and natural resources, as many threats to environmental sustainability are posed by human behaviour. In particular, environmental psychologists identify behaviours that can and should be changed to improve the quality of the environment, identify factors that influence those behaviours, and design and evaluate interventions to change them.

Knowing the value of an individual helps environmental psychologists develop intervention strategies. For example, if the primary concern of an individual or group is selfish, you can focus on interventions that emphasize the personal benefits of environmental protection, such as reducing utility bills. Emotional connections with nature are important predictors of well-being and ecological behaviour. By helping people connect with nature, environmental psychologists promote sustainable behaviour and general well-being.