Over the ages, there have been several architectural movements and styles. Architecture unique to a given region is referred to as regionalism. It is mostly derived as a reaction to the topography, context, and climate of the area. It is customary and frequently stems from years of speaking in the local dialect. The unique characteristics of that region, including its climate, available resources, skilled labor, culture, and way of life, influence regionalism-based design. However, regionalism and critical regionalism differ in a few significant ways.

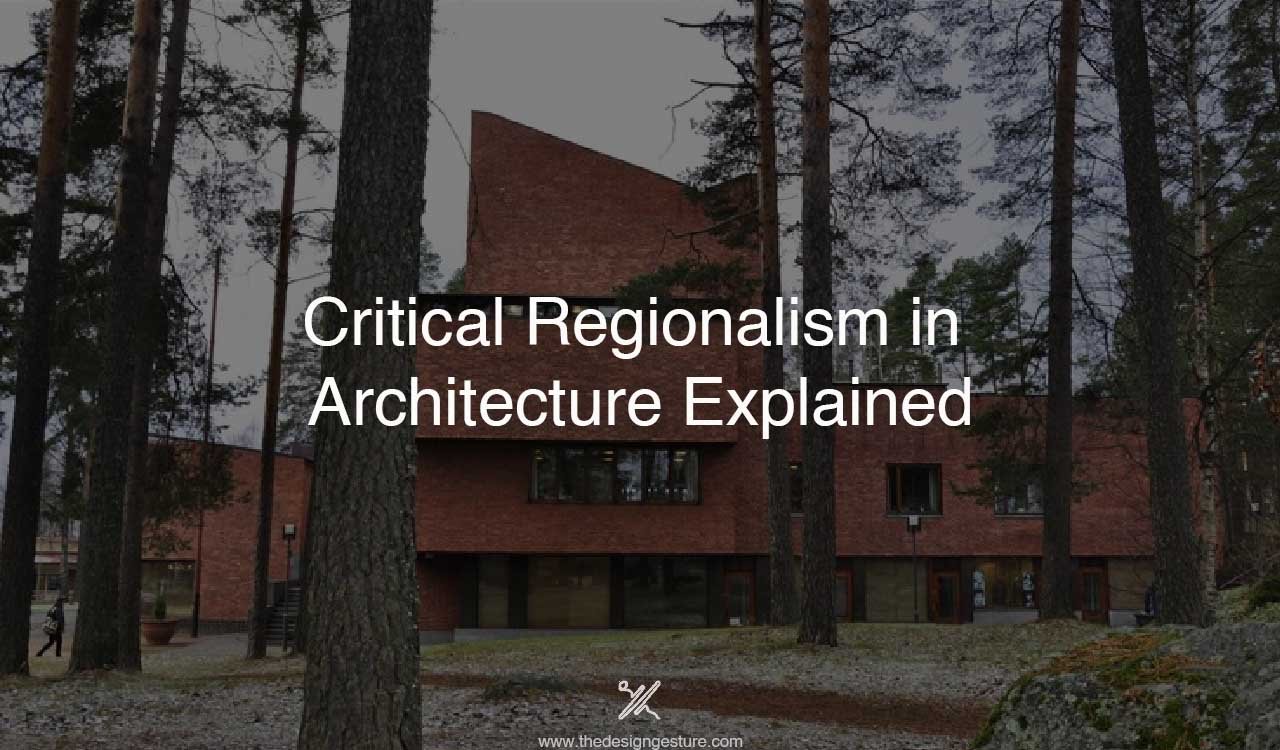

Architectural theorists Alexandra Tzonis and Liane Lefavire defined critical regionalism as a concept in the early 1980s. Critical regionalism can be simply looked at as the balance between the needs and growing modernization. Additionally, according to the theorist Kenneth Frampton, critical regionalism is a solution to the modernized approach of design in the regional context. The main idea for critical regionalism is the contextual response in the architecture. The architectural response should be on the history, place, climatic conditions, topology, ecology, culture, and traditions, of the particular region.

As a result of globalization, critical regionalism was a response to the mass-produced architecture that was rapidly irrespective of the context. The period showed that irrespective of context architecture with standardized material and module physicality can be designed to impact the overall society with the mental health of the residents. The standardized architecture developed a sense that was of placelessness where you see similar buildings irrespective of function and location. The critical regionalism was the approach to balance these practices with the need.

Table of Contents

Critical Regionalism as a Concept (Kenneth Frampton)

Kenneth Frampton, an architectural theorist, published a lot about regionalism, especially critical regionalism. The necessity of critical regionalism is clearly explained in two of his essays, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance” and “Ten Points on an Architecture of Regionalism: A Provisional Polemic.”

The primary topics he discusses in these writings, center on the difficulties architects have in striking a balance between regional and global specifications and conditions. These opposing behaviors are likened to oppositional twins by Frampton. One twin stands for the human and contextual elements of regionalism, including the local topography, natural features, cultural and environmental elements, and materials. The term “other” refers to general, universal elements including information, ventilation, ergonomics, artificial lighting, and visual communication in space design. He suggests that critical regionalism is the result of contrasting these two elements.

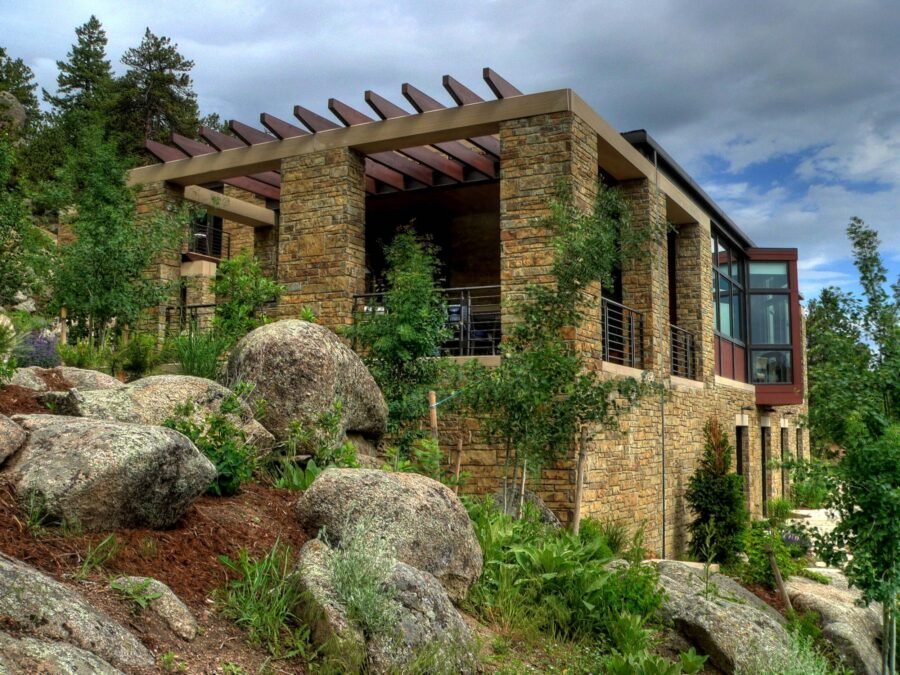

Critical regionalism’s guiding principles emphasize designing for the local context rather than transferring existing elements and superimposing them onto any given setting. Nonetheless, it acknowledges the potential for total reuse of architectural objects. Rather, it suggests reconsidering how the same components are used in a regional setting. The idea of tactile sensitivity—which combines regional and global influences to improve a space’s experience—is supported by critical regionalism.

Cultural Regionalism: Six Points in Architecture

Culture and Civilization

Once modernism took hold, the attention to the outer spaces and the connections between them decreased and was concentrated on the inner areas. Kenneth Frampton tells us that we must create a landscape that links the interior to the exterior without ignoring the surrounding environment. These days, when developing a new building, we have to take the climate into account. The design has no meaning in isolation. Accepting the broad principles of modernism while keeping the building’s geographic setting in mind is essential. Understanding the geographical and historical context of the building sector should be crucial.

The Rie and Fall of Avant Grade

The movements were a reaction to the gothic aesthetic and the decidedly negative tone that art and craft concepts took. However, to interact with modern society, one must engage in both political and scientific logic. Critical regionalism implies a dialectic relationship with nature that is more direct than the formal, abstract traditions of modern avant-garde architecture allow. Frampton disagrees with the ideals of both postmodernism and modernism. While pointing out Modernism’s limitations, he also criticizes the neo-traditionalist branch of postmodernism for attempting to break free through avant-garde themes. However, Frampton believes that modernity must be preserved, but only through the lens of the Postmodernist critical thought tradition.

Critical Regionalism and World Culture

Critical regionalism meets universal needs by presenting the local vernacular, which has been lost due to avant-garde movements. Here Frampton advised Southern countries to reexamine their traditions and return to discover their historic values, beliefs, and identity, as well as to infuse a sense of ownership in architecture. He proposed employing contemporary architecture to reinforce regional identity. He wanted to focus on things that were relevant to the setting. Like John Utzon, modern architecture employs modest regional materials.

The Resistance of Place – Form

While designing, the focus is on considering the place with its surrounding regions and the identity of the place. Additionally, concerns regarding the whereabouts of humans are inseparable. The physical space of the region and the location where communication between people is not the same thing. The spatial organization of a building should be solved in terms of its relationship to external qualifications of place, such as its entrance, exits, and circulation.

Culture Versus Nature

Frampton explained that critical regionalism requires a closer engagement with nature than contemporary architectural traditions. While examining the significance of these two aspects in the construction of an architectural building that is linked to culture and the landscape. When developing an architectural structure for the environment, both of these aspects should be combined to develop a relationship between their conceptions, rather than creating a freestanding item. Geographical components and cultural history will have a significant impact on the ecosystem, climate, and symbolic qualities of place. This is what causes the “place-form” stability between the environment and culture.

The Visual Versus Tactile

Frampton states that when designing, both the visual and the other five senses should be considered. The cooperation of all senses contributes to architecture’s depth and uniqueness. This approach encourages the use of all materials that target all senses and allow for a wide range of emotional responses.

Critical Regionalism strives to design buildings that include culture, context, light, and cooperation with all senses, and are connected to local architecture using modern technologies.