Table of Contents

Bunkers And Their Origin

From the sand-filled hazards on golf courses to German dugouts becoming prevalent during World War, bunkers have taken several forms, eventually keeping their cold, rigid nature. It was only until the second World War that bunkers would be recognized as the cemented dugout created to hold arsenal or house humans for protection. Architecture thus took a form to restrict not only shear impact from heavy weaponry but also interaction with humans. Buried in grounds or standing, behemoth forces of concrete-like watchtowers waiting to be inhabited, bunkers could not safeguard humans, but also a tumultuous history.

Time Capsules

Through forms themselves, one can view these structures as frozen in time awaiting a new catastrophe. For many years, World War Two bunkers around the world were regarded as an ugly remnant of a bygone era, with little thought given to their historical and architectural significance. As the French architect and philosopher, Paul Virilio rightly says in his famous book Bunker Archaeology- “The bunker is less a warning about the opponent from the past than about the war of today and tomorrow: about total war, the risk which is present everywhere, the immediacy of the danger, the amalgamation of what is military and what is civilian, the homogenization of conflict.

These military seeds were sewn across cities and continents grow and an unsettling fear of what is lying ahead. Of what society retained from pure chaos, thus psychologically affecting its surrounding. To the veterans, these structures are like fossils reminding of a tumultuous era. For the residents, it’s a physical reminder of the history, their connection to their lineage, in certain cases, the generational trauma. An almost poetic outlook on these forms of resistance, death, and destruction has been the creation and sustenance of art. Many of these bunkers have been housing arts, becoming art themselves.

Arthouse Of Cultures

Holding onto the beauteous aspect of world history one panel at a time. While some house art pieces several have changed to become art itself. To some, this seems as near demolition of such historic time capsules others indirectly question the very purpose they were created for. Having been sliced open, they’re susceptible to the forces- nature, and mankind. Uprooting the very fabric of its existence in a way, this is the artists’ way to take over these cold forms- ripping them apart from their spines and making their delicate cores- the living spaces, vulnerable. Bunker 599 is an example of this wonder.

Bunker 599

The New Dutch Waterline (NDW) was a military line of defense in operation from 1815 until 1940 that used artificial flooding to protect the cities of Muiden, Utrecht, Vreeswijk, and Gorinchem. An impregnable bunker with historic significance is ripped open. Because of the design, the tiny inside of one of NDW’s 700 bunkers, which is ordinarily hidden from view, is now visible. The white staircase merges to form a thin white line, slicing right through the New Dutch Waterline bunker trailing onto the quiet lake has converted it from a remorseful mound into a place of meditation. Aligning oneself to the white line and making oneself steady the same way. Eventually gaining its recognition as a national monument.

Albanian Shelters

Wherein Albania the beautification process extended to communist structures and residential buildings, the bunker style entrance is surrounded by swatches of paint everywhere. Instead of wrecking it all down, the artists collaborated to use these historic places as canvases while surrounding areas saw city workers plant over 55,000 trees hoping to rejuvenate a solemn area. And so it did. With local police noticing a lowered crime rate, people noticed an increase in a combined sense of joy and pleasure. The squares that held riots to the bunkers that kept an eye for caution and warning both have now become places of jocund interaction and communion.

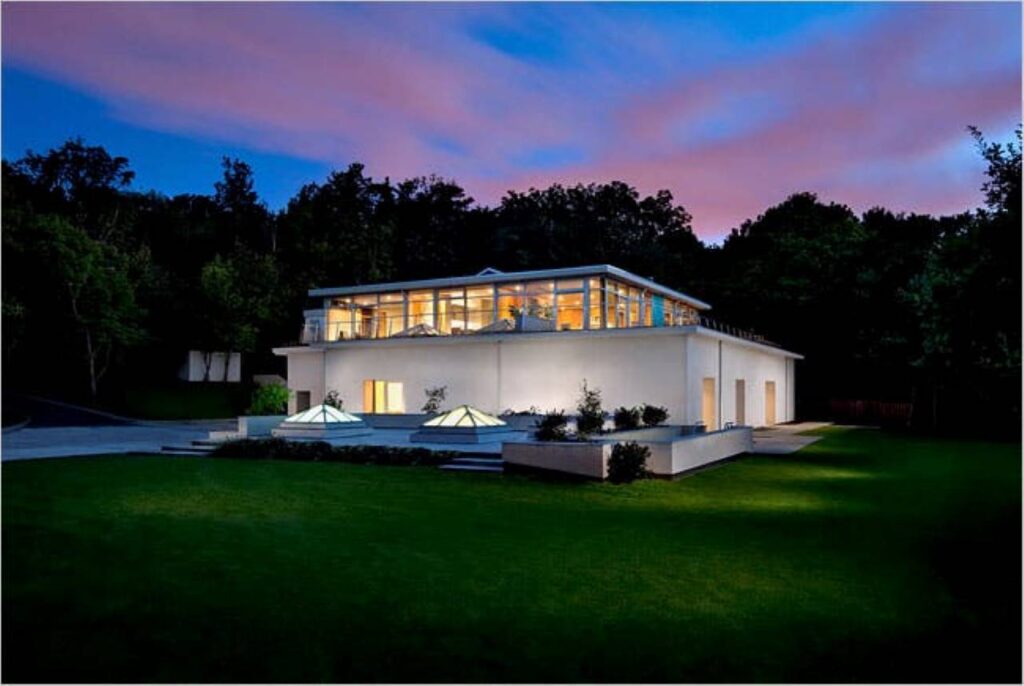

Seafield House

Seafield House, an austere example of contemporary architecture just a quick jog from the Finchley Golf Club in the North London district of Barnet, has a sad past that belies its beauty. The British government employed 5 foot or 1.5 meters, thick walls to construct the tower in the early 1950s to safeguard military chiefs in the event the Cold War turned nuclear. The strong concrete walls of the bunkers made modifications difficult. To carve out windows and outside entrances, diamond-tipped chainsaws and drills were employed in the end. Because it was all about nuclear apocalypse and a Dr. Strangelove scenario, the whole concept was to construct an architecture of life from the architecture of death.

Data Storages

The bunkers have continually stood the test of time, even when it comes to their operation. With the booming growth taking place in data creation, networking and storage, it calls for a physical realm where mega units of this data can be stored or the machines measuring and churning this data out can be kept safely. And thus we see bunkers becoming core data storage units. And thus, for someone trying to access this data digitally, they’ll witness what some assume is a virtual bunker because of the difficulty and resistance to outside invasion.

The Revival of The Refuge

In some way, what continues to ooze a lingering sense of dread- be it of what the past had or the potential that a future might hold, the world hopes to not use these bunkers for what they were sued for. Instead, they are being used as a resource to the citizens. For art, history, and for data. Bunkers have become a silent iconography to war. They create a solemn feeling among citizens affected by war, not entirely mournful but an odd sense of martyrdom. As they remain silent waiting while artists rethink them as canvases for their art.