Introduction

Sandy golden beaches, tropical forests, and perennial rivers with paddy terrains in sultry heat create a satisfying canvas of the great Southeast Asian region. One can easily distinguish as well as picture SEA, consisting of many early civilizations of the world, not only because of the great heritage these treasure but also the culture and rituals instilled in the people of this region.

Living in Southeast Asia

We, as people, are carriers of many innovations including art, values, and architecture of course. In a region where stones are worshiped, water is sacred, food is more than just fuel for the body, houses hold a special emotional status for many people here. It’s not just a place to retire at night for a good night’s sleep, but they somehow breathe with the dwellers, inspire families, welcome tired souls happily, and whatnot.

Be it the Grand Palace of Bangkok or the house on the stilts of Myanmar, the feeling instilled in the person residing is the same. The houses built here are more like static humans. A separate space for stories to recite, to cook fresh aroma, and to change attire all jam-packed in the same old house.

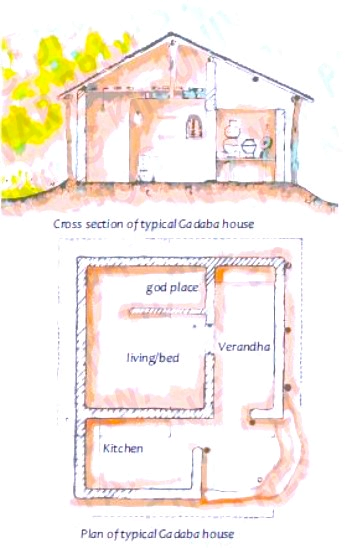

Uniqueness can be more recognized when the houses we live in are traditional, raw, and stylized with local materials. A village in South Odisha bordering Andhra Pradesh houses the Bonda tribe majorly. Primarily erected with mud and capped with clay-tile roofs homes in the village of Bhaliapadar have a distinct character. Usually, one room is used as a living area to sleep in, and the other as a kitchen. They do also have ample space for an elevated platform or verandah.

Upon the verandah wooden staffs stand to support the roof. Although small, they are simple and minimalistic. Even some more evolved tribes like the Santhals and Gandabas in the region have kept the ancient traditions alive, which is evident in their homes. And since all the houses in a locality are similar in size and character, they directly or indirectly shape the identity of the place. Scarlett with a tint of ochre painted on the outer walls of the houses by Santhals along with thin strokes of blue for sheer detailing.

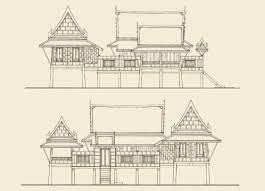

Entirely or largely depending on agriculture as a profession and living it impacts houses in South East Asia highly. For example, in traditional Thai housing, we can witness the bamboo raised floor to avoid floods. They should be able to accommodate both goods and animals. Moreover, different kinds of bamboo, wood, and prefabricated panels were used in Siamese villages. A typical Siamese wooden dwelling has separate rooms organized under a single, huge roof. Before you step into the house, a water jar is kept at the bottom of the steps to wash feet; and all the rooms oversee a central platform. Houses were set to expand for future generations, that is extra rooms for younger ones of the family.

The social congregation is an essential aspect of life in the island countries of Southeast Asia. Some ethnic groups in Indonesia practice such traditions even now, through their housing systems. For instance, the Karo Batak house is a meeting shelter for the bachelors of the village, who use it as a recreational space. Resembling the basic pyramid structure, the Karo Batak house is thatched with ijuk, and the roofs are decorated with painted interwoven split bamboo. Perhaps, buildings erected by this community are very complex and have highly intricate details. Thus, a few renovated heritage resorts adapted the styles of Karo Batak houses in their cottages.

The sanctity and sacredness of lifestyle can today be clearly seen in villages and countryside areas of nations running towards modern systems. In a book named ‘ARCHITECTURE OF SOUTH EAST ASIA’, there is an independent section dedicated to travelogues written in villages for brief periods. One of those encounters talks about the Burmese villages of Meeryoungyai and Nyaung-U, on the banks of Irrawaddy by R. Talbot Kelly.

The author along with his companion experienced traveling with the help of coolies, bullock gharries, and ponies to the serene deep woods. To their surprise, women and young girls carried out the loading and unloading of heavyweights to transfer them from one bumpy ride to the other. The houses or dak had typical features: primarily made of bamboo, however many had eng wood principal timbers all raised on four to six feet long piles to protect them from floods, snakes, and malaria.

Floors weaved out of split bamboo or thatch of elephant grass, or ‘thekke’ or bamboo mats called ‘tayan’. Tayan can serve as walls for modest dwellings, though the walls nearing the streets are usually exposed, displaying the interiors of the house. The domestic arrangements are generally composed of naked young children running and jumping accompanied by pigeons, geese, and poultry underneath the houses. And as dusk hits, the sound of returning bullock gharries and carts meets the sweet aroma of Burmese kitchens. The houses are aligned with each other creating ample roads in between them.

Although strong roots of beliefs, cultures, traditions, and linguistics of more than three hundred fifty ethnic groups reside here, many fast-paced globalization trends compel her to change and match contemporary architecture standards. Since the early twentieth century, the region has experienced many transformations because of the rapid colonization by Westerners. Powerful influences imposed on natives left a non-perishable marvel of colonized buildings then.

Streets in old Kolkata have many solid red and white administrative buildings with tall, slender Doric columns. However, if observed closely, westernization has led indigenous construction techniques to take a back seat, and slowly vernacular architecture became sparingly known to even locals, which as a result has deteriorated the climate responsiveness and user-friendliness in our homes.

What we shape is given birth by what shapes us. So, the architecture of tomorrow that we need to design needs to receive and learn from the architecture of yesterday. The vernacular architecture of any place is the specific identity of that area. It’s somewhat related to traditional buildings but vernacular architecture is generally an offspring of the easily available local materials. So to respect this kind of knowledge, architects should thrive and try their best to design a worthy product to live in.