Table of Contents

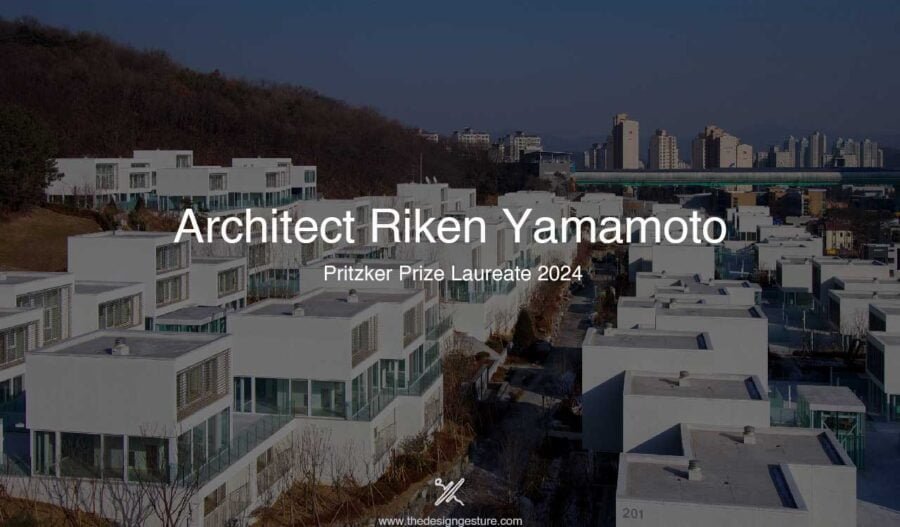

Pritzker Prize 2024 Laureate

Architect Riken Yamamoto was awarded the Prestigious Pritzker Prize this year, for his five-decade-long contributions to the built environment and his concern for the community that habited it. What it takes for an established architect who has won many prizes to rather confess “I am not very good at design”? Interestingly Yamamoto did confess so in 2012, in the foreword to his monograph. Quoting Yamamoto

“I am not very good at design … I am well aware of that. However, I do pay careful attention to what is around me. By what is around me, I mean the surrounding environment, the existing local community, circumstances in contemporary society …”

Humility, at its peak, isn’t it? Especially with star architects in the background. He is another humble pioneer from the Land of the Rising Sun, awarded the “Nobel of Architecture”. True Humility is from within, but the Jury highlighted the humility not only in Yamamoto but also in his works. The intrinsic humility in his life, design philosophy, and works is explored below.

Personal Life Influencing his Design Philosophy

Beijing-born Japanese Architect Riken Yamamoto shifted to Japan post World War 2, where he was introduced to the Japanese Machiyas and its distinct private-public space interaction while still fulfiling the needs of the family, which later became a signature in all his designs. He graduated with a Bachelor’s degree from Nihon University in 1968 and received a Master of Arts in Architecture from Tokyo University of the Arts in 1971.

Architect Hiroshi Hara, his Mentor who was against Modernism and Metabolism had significantly influenced Yamamoto’s design direction. Moreover, in general, most Japanese architects who were born in the 1940s including Tadao Ando, and Toyo Ito were in their twenties when the Metabolist period was developing in Japan, and within a decade, there were questions against post-war Metabolist ideas and student protests. Influenced by these, this generation of architects deviated away from Modernism and Corbusian ways of the mass production machine image and shifted their design strategy to light and floating images since the 1970s, and Yamomoto born in 1945 was no exception to this.

After graduating, among architects who travel to visit explicit architectural structures, Yamamoto traveled with his mentor Hiroshi Hari across countries and continents by road, visiting villages, absorbing the essence of vernacular architecture, and understanding communities and cultures. After exploring Europe to South America, followed by Iraq, India, and Nepal, he concluded that the connection between private and public space in the Japanese Machiya, the public/private threshold was universal though the appearances (form and materials) were different.

A Design Philosophy, Rooted in Community

In 1973, Riken Yamamoto established his own practice, namely Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop. He realized the potential in such thresholds to build and strengthen local communities, and based his philosophy on transparency; ‘transparency, in form, material and philosophy’. Yamamoto is on a mission to erase words like trespassing, private property, privacy, boundary wall, etc, from the dictionary.

Irrespective of the building’s categorization as private or public, Yamamoto always inserted a public space that increases the chance for encounters and awakens the community spirit. According to him privacy only pushes the communities away from each other. He believes it is still possible to maintain privacy and respect the freedom of each individual, even when communal spaces are created.

His Notions about Housing

Though Yamamoto has worked on projects of various scales and functions, his residential projects were groundbreaking, fundamentally questioning the privacy often associated with homes. He has openly expressed his dissatisfaction over standardized housing, which was intended to create standardized families and thus a standardized working force. He sees this approach of ‘one house = one family’ as a failure of the Japanese system of governance.

His criticisms of standardized housing would be relatable if the notions of traditional Japanese housing were recollected and understood. His contemporary notion of housing was born by fusing the past and considering the need for socializing in the present is explored through analyzing some of his projects.

Yamakawa Villa was one of his first projects for one of his first clients, Mr Yamakawa. The client wanted a villa with a spacious terrace as big as a living room where he could spend time only in the summers. Yamamoto designed the whole Villa as a terrace dotted by clusters of built cubic volumes covered with a gabled roof. In this project, the terrace was made the foreground and the built elements that housed the room, bathroom, toilet, and kitchen were made the background. Transparency was at the core of the project and with background-foreground reversal this project seems like a public project rather than a private holiday home. His subsequent housing projects followed a similar approach.

The Ishii House was designed by Yamamoto to accommodate two artists in Kawasaki. One of its unique features was a pavilion-style room that extended outward and served as a performance stage, with stepped seating arrangements. The rest of the living spaces were located underground. His ideas were accentuated in his first social housing project, built in Kumamoto in 1991.

In this project, he used a central square that can be accessed only by passing through one of the 110 homes to accentuate the communal heart while respecting the privacy of individual families. He envisioned social housing as more than just a space where families live and raise children. He thought it was necessary to open up housing to the local community by inserting communal spaces and activities in order to ensure that even people who inhabit houses alone won’t remain isolated.

Unveiling the Philosophy in his Other Projects

He has extended the idea of transparency and communal spaces in his other projects too. For instance, in his campus for Saitama Prefectural University in Koshigaya, built in 1999, Yamamoto fused the nine buildings into a series of terraces that serve as both walkways and communal spaces, leading to glass volumes that allow views from one classroom to another, and from one building to the next, encouraging visual interaction and interdisciplinary learning.

Further, his fire station in Hiroshima, built in 2000, is a seven-story box, clad with glass louvers on all sides, allowing a direct view of the action taking place inside from the street. He believed that heroic civil servants should be celebrated in full view and that inspired him to design so. He applied similar social principles irrespective of designing elementary schools, university campuses, or art museums.

Conclusion

Yet again another solo male practitioner awarded the Prestigious Pritzker Prize is stirring controversy. The awarding committee is being bombarded with questions on gender neutrality and whether it has actually evolved to the extent that the profession itself has. Amidst controversies and concerns, what really fetched Architect Riken Yamamoto the award is worthy of attention, especially in the hour.

Quoting the Jury Chair Alejandro Aravena who was also a 2016 Pritzker Prize Laureate “One of the things we need most in the future of cities is to create conditions through architecture that multiply the opportunities for people to come together and interact. By carefully blurring the boundary between public and private, Yamamoto contributes positively beyond the brief to enable community…He is a reassuring architect who brings dignity to everyday life. Normality becomes extraordinary. Calmness leads to splendor.”

Can architecture do justice to a commoner’s daily life? What role does architecture play in community building? Questions that Architect Riken Yamamoto has answered and left the rest of the community to ponder upon!

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Q. Who won the Pritzker Prize winner 2023?

David Chipperfield won the Pritzker Prize winner 2021.

Q. Who won the Pritzker Prize winner 2022?

Diébédo Francis Kéré won the Pritzker Prize winner 2021.

Q. Who won the Pritzker Prize winner 2021?

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal won the Pritzker Prize winner 2021.