Table of Contents

Introduction

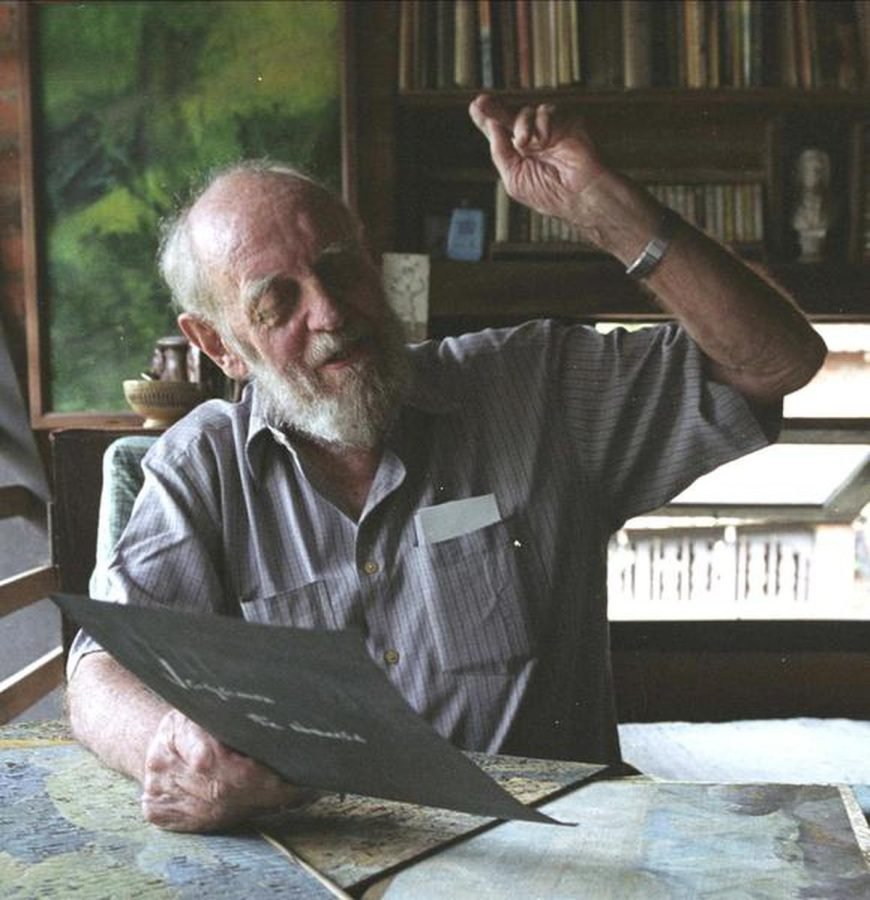

The incredible tale of British-born architect Laurie Baker, who dedicated his life to serving the housing needs of the impoverished, is told in this account of his architectural journey. While he may have followed a successful profession back home, fate had other ideas. When Baker was first exposed to the ideas of Mahatma Gandhi, his life’s work took a completely different direction. This encounter would serve as the impetus for a lifetime of commitment to serving the “ordinary” people.

Influences: Music and Gandhi

Baker’s early influences were as diverse as they were profound. He was raised surrounded by the melodic sounds of his mother, Milly Baker, an organist, and father, choirmaster Charles Frederic Baker, as part of a family steeped in Western classical music. His background was heavily influenced by music, which would later have an indirect effect on his architectural philosophy.

However, Baker did not subscribe to Friedrich von Schelling’s famous assertion that “architecture is frozen music.” Instead, he drew a unique parallel between Indian architectural traditions and the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach, one of his favourite composers. He believed that Indian designs made vital use of light and shade, a characteristic shared with Bach’s music. This connection between music and architecture provided a distinct foundation for Baker’s creative vision.

Gandhi’s Influence: A Turning Point

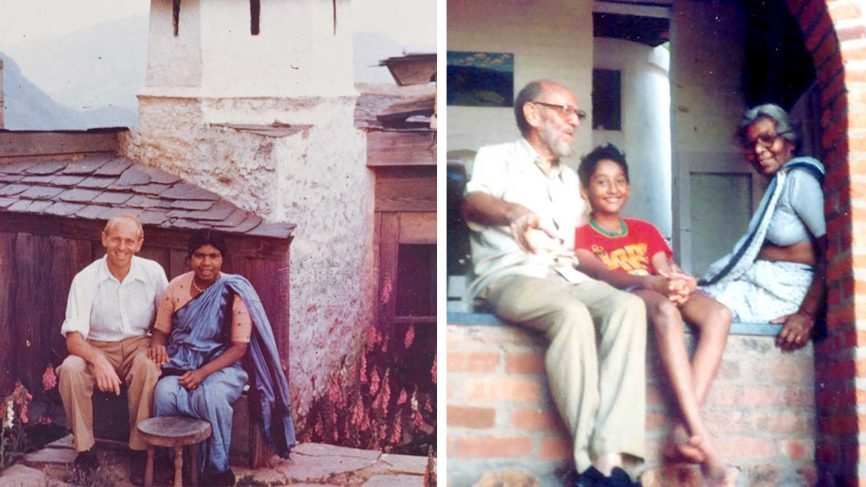

While Laurie Baker’s upbringing introduced him to music, his life was forever changed by an encounter with Mahatma Gandhi. In 1943, as he awaited a journey back to England in Bombay, Baker met Gandhiji multiple times. These encounters permanently altered him. The words of Gandhi, “You are bringing knowledge and qualifications from the West, but they will be useless unless you try to understand our needs here,” truly resonated. It was a time when the Quit India Movement was in full swing, and the call to serve the underprivileged in the villages struck a chord with Baker.

These encounters with Gandhi and the call to service led Baker to return to India in 1945. His primary mission was to serve leprosy patients. With limited funds and resources, he embarked on the transformation of old houses into modern hospitals. This marked the beginning of his hands-on approach to architecture, setting the tone for his future works.

The Baker Style: Simple, Contextual, and Sustainable

Baker’s architectural style, often referred to as “The Baker Style,” is characterized by its simplicity, contextual relevance, and sustainable practices. His deep understanding of the lives of ordinary people and the conditions they faced led to an exploration of regional architectural ideologies. Baker believed in workability and affordability in his designs, ensuring that they responded effectively to the users’ needs.

Embracing Regional Natural Building Materials

At the heart of Laurie Baker’s architectural philosophy was the use of locally available materials. He believed that these materials had a unique character that enriched the built environment. Bricks, especially those made of burnt mud, held a special place in his designs. Baker likened bricks to faces, each with its shape and color. He appreciated the slight variations among bricks, which, when used in large numbers, contributed to the character of a wall.

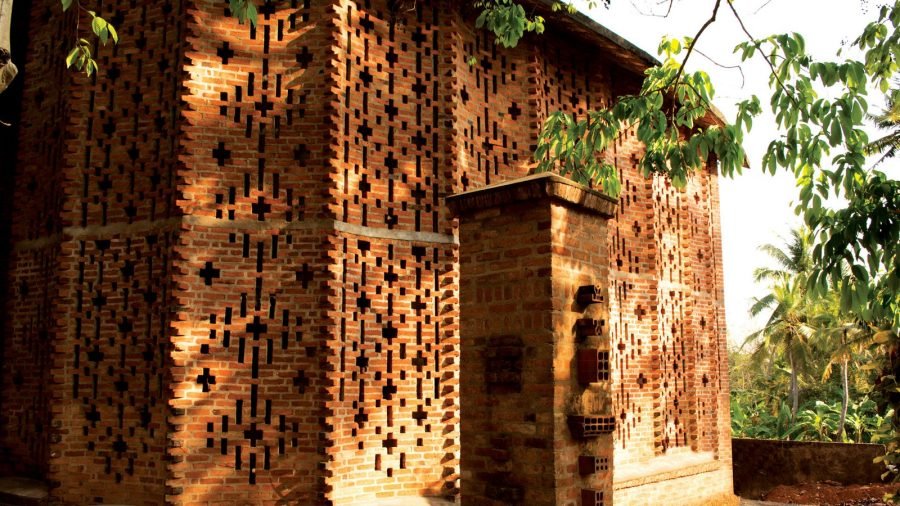

One of Baker’s notable practices was the use of exposed brick in his designs. He saw no need to cover these characterful creations with plaster, which he found dull and characterless. The contrast of textures from brick, stone, concrete, and wood added depth and richness to his architectural works. The result was not just buildings but living, breathing structures that connected with the environment and the people who inhabited them.

Innovative Use of Materials

Baker’s commitment to sustainability extended beyond just the use of natural materials. He was an innovator in adapting foreign inventions that reduced material and energy consumption while enhancing the insulation of his buildings. Two notable examples were rat-trap bond masonry and filler slabs.

Rat-trap bond masonry incorporated insulating voids within brick walls without compromising their load-bearing capacity. This innovation allowed Baker to create structures that were better suited to the climate and required fewer resources.

Filler slabs, another of Baker’s adaptations, replaced the concrete in the non-compressive bottom part of structural slabs with two discarded roofing tiles placed one on top of the other. This technique not only reduced cement consumption but also provided valuable insulation through the air trapped in the hollows of the tiles’ corrugated profiles. Baker’s pragmatic approach to design allowed him to integrate these techniques seamlessly into his architectural style.

Functionality and Integration with Nature

Baker’s architectural approach emphasized the functionality of spaces and their seamless integration with the natural environment. His designs often featured internal courtyards for natural ventilation, which was especially important in hot, humid, and rainy regions like Kerala. Baker also extensively used perforated external brick walls, known as “jali” in North India, in place of the traditional (and more costly) wooden trellises of Kerala. This not only allowed for natural ventilation but also created a unique visual appeal.

Cost-Effective Construction

In contrast to conventional architectural practices, Baker’s approach sidestepped the need for architectural assistants and intermediaries such as contractors. His design-build method was founded on mutual trust between the architect, client, and craftsman, eliminating unnecessary costs and ensuring a more efficient and delightful construction process.

This approach also opened the door to reusing discarded materials from old houses, which were available at very low cost. Baker’s commitment to affordability and sustainability was evident in every aspect of his work.

Legacy and Inspiration

Laurie Baker’s architectural philosophy and practices have left an indelible mark on the industry. His commitment to simplicity, sustainability, and the needs of ordinary people continues to inspire architects around the world. The Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies in Trivandrum serves as a living testament to his legacy, providing a platform for young architects to learn about and further develop “The Baker Style.”

Notable Projects: Celebrating Baker’s Vision

Laurie Baker’s architectural brilliance is perhaps best exemplified in his notable projects, which showcase his philosophy in action.

Loyola Chapel: Where Light and Spirituality Converge

The Loyola Chapel in Thiruvananthapuram, designed by Laurie Baker, defies the conventional image of a chapel. Its exposed brick walls and intricate Jali patterns create a unique ambiance, where the introduction of light towards the interior and its indirect reflection illuminate the space in a language of its own. The chapel’s design masterfully combines the spiritual with the architectural, making it a testament to Baker’s unique approach.

Indian Coffee House: Affordable Dining with a Twist

In the heart of Thiruvananthapuram, the Indian Coffee House stands as a testament to Baker’s effective use of minimal space. The cylindrical volume with Jali-lit walls and a spiral ramp provides an efficient dining experience. It’s an excellent example of cost-effective techniques that keep the space accessible to the common population.

The Hamlet: Baker’s Personal Manifesto

Laurie Baker’s residence, known as The Hamlet, stands as a personal manifesto of his architectural principles. Curvilinear exposed-brick walls, heat-reducing Mangalore-tile roofs, and timber elements define the space. The building is a reflection of Baker’s philosophy, where simplicity and contextuality reign supreme.

Hamlet’s location on a steep mountain slope in Nalanchira, Thiruvananthapuram, adds to its uniqueness. Carved out of the rocky hillside, it appears as if it has ‘grown out of the earth.’ The building’s integration with the natural landscape is a testament to Baker’s commitment to harmonious coexistence.

Laurie Baker’s engagement with the entire architectural process, from initial sketches to the building phase, was deeply personal. He found joy in interacting with the workers, the materials, and the building itself. Witnessing the transformation of his drawings into tangible structures on Indian soil was a source of immense satisfaction.

The Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies: A Continuation of the Legacy

In Trivandrum, the Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies acts as a link between architecture’s history and future. It preserves Baker’s ideas and gives the next generation of people a chance to learn about “The Baker Style.” Contextualization and local knowledge are key components there, as they were throughout Baker’s distinguished career.

Conclusion

A clear example of the value of sustainability, user-friendliness, and a thorough comprehension of the requirements of the typical person is Laurie Baker’s architectural career. His architectural philosophy, which drew heavily on Mahatma Gandhi’s teachings and music, has had a lasting impact on the sector. Thanks to his inventive material choices, economical construction methods, and appreciation of the natural environment, Baker remains an inspiration to architects across the globe.

Notable undertakings such as the Loyola Chapel and the Indian Coffee House are examples of how strong Baker’s notion is. His commitment to simplicity and context is evident in his house, The Hamlet. Laurie Baker demonstrates via her work how architecture can be a vehicle for social change, environmental sustainability, and artistic expression.

The Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies continues its legacy by providing opportunities and fostering an appreciation for regional understanding, affordability, and utility among the next generation of architects. Anyone who believes in the transforming potential of architecture might find inspiration from Baker’s architectural journey. In his own words, “We must never lose sight of the fact that 20 million families live in abject poverty, let alone enjoy the privileges of architecture. We should be ashamed for allowing these numbers to rise.” Laurie Baker devoted his life to bucking this trend, and his influence can still be seen in the structures and ideas he inspired.