In all phases of our education, we’ve heard and realized the reality within the saying ‘Rome wasn’t inbuilt a day. Architects always progress in their design step-by-step, reviewing, changing, and improvising whenever.

The role of architects and their work in shaping communities has been much debated over the years. And though it’s since been proven that its influence isn’t as direct and complete as once thought, there’s little question that architecture influences communities in different ways.

Similarly, architecture may not have a social impact on the world in one single moment, but it surely has the power to influence the surroundings, little by little, every day. From changing the smallest element in design to shaping and designing large spaces, architects find out the ideas of moulding society in different ways.

Let’s discuss some of such projects built in India.

Table of Contents

Design Projects That Are Making Serious Social Impact

Kalkeri Learning Centre, Kalkeri, Karnataka

Kalkeri Sangeet Vidyalaya is found in a quiet valley near the town of Dharwad in Karnataka, South India.

Established on three acres of land a brief distance from Kalkeri Village, the varsity comprises straightforward buildings made up of traditional materials. In this peaceful setting, the youngsters enjoy the tranquillity necessary for their academic studies, music practice, and humanistic discipline activities.

The intent was to make an adaptable set of spaces for the youngsters, within the constraints of a decent budget, logistics, and available resources. It was an exercise in creating a learning environment that’s resilient, energy-efficient, and richly layered while building in scalability and replicability.

Over 200 children and shut to 100 staff and volunteers use the training complex as a hub of daily activity. While the spaces are used as art workrooms, library, and staff spaces, the semi-enclosed spaces are regularly used as out-of-door classrooms for music and theatre, community meetings, and improvisational performance spaces.

Kutch Earthquake Rehabilitation, Kutch, Gujrat

Bhuj was hit by a deadly earthquake in 2001. The state government didn’t have guidelines for construction on earth technologies which meant that the affected villages couldn’t rebuild in their traditional format.

Hunnarshala, together with the government, tested earth technologies and helped issue guidelines for the same. Later they also worked towards issuing technical building guidelines for un-stabilized earth technologies.

Along with the guidelines, a manual for masons in Gujarati was prepared to educate them about safe construction practices. These technical guidelines and manuals enabled over 100 villages to rebuild using earth technologies.

Hunnarshala along with other partner organizations of Abhiyan, like Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan (KMVS) worked closely together to train the rural population in Bhunga construction so that they could rebuild their homes in a way that did not compromise on safety also as their cultural expression.

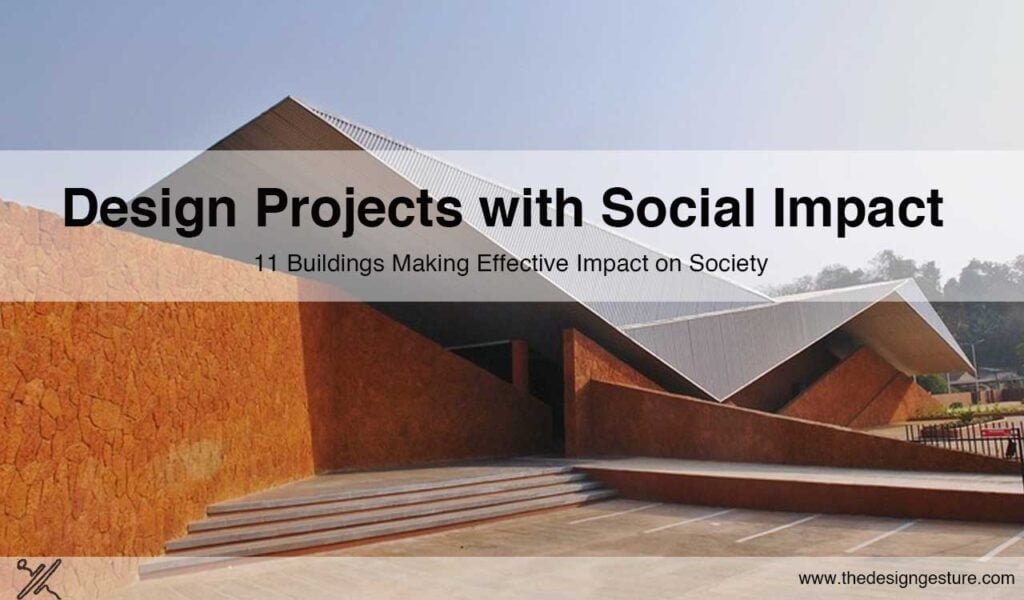

Avadh Shilpgram, Lucknow, India

Genrally, urban bazaars’ architecture works on a scheme of a mélange. The visual mélange produces an architectural scenario for the activity of leisure and pleasure, an indulgence in shopping also because of the feeling of partaking in actions associated with craft and culture. It creates a civic compass that inserts itself within a distinct reality; like in a recreation demesne, a bubble of reality within the everyday reality of the megacity outdoors.

During the planning process, the layout of the twenty-acre Awadh Shilpgram developed organically from the commercial, cultural, social, and leisurely interactions of individuals.

An elliptical form enables a smooth corner-free rotation; it narrows down while twisting inward and emulates the viscosity and sprightliness of the Lucknowi Stores of yesterday’s; the stores with the thoroughfares that got precipitously narrower. The built environment is an interpretative collage, a gesture of saluting the unique traditional architecture of the Roomi Darwaza and, therefore, the Imambaras.

Sufficient daylighting, proper cross ventilation further adds the dimension of comfort to the design. Its articulation has been realized through a contemporary interpretation of traditional rudiments of bends and Jaalis.

The unique concept alongside the shape, scale, materials, and elements that render the architecture give an iconic building to the town of Nawabs and therefore the people of Lucknow.

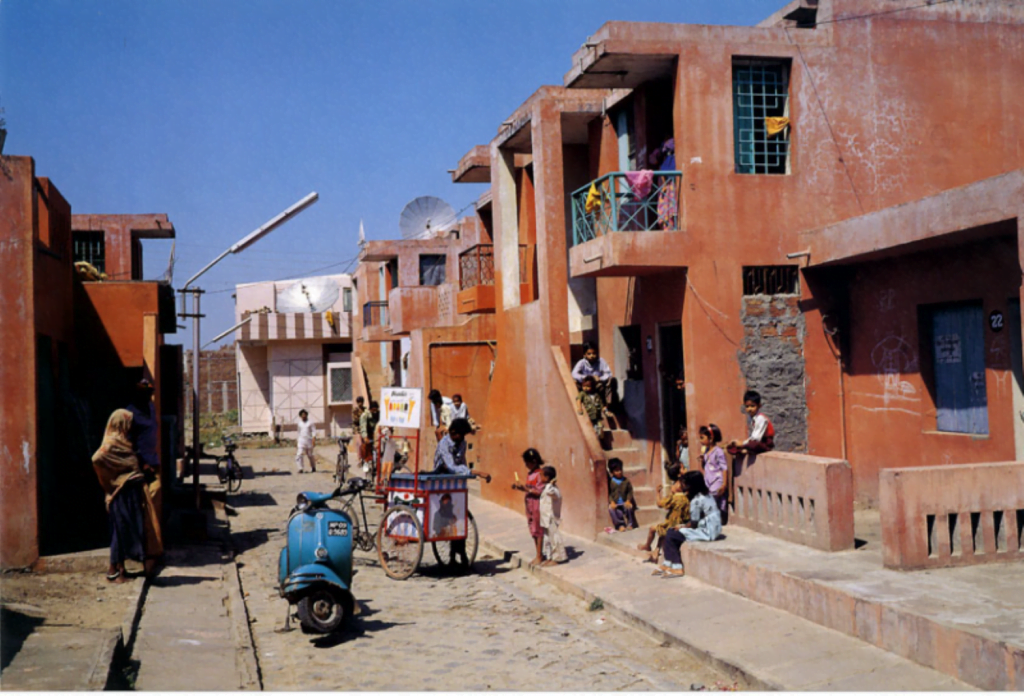

Aranya Housing, Indore, Madhya Pradesh

Indore, India, within the early 1980s, was facing a shortage of housing. It had been estimated that roughly families were homeless or living in illegal agreements. The Indore Development Authority initiated a reasonable public housing for 60,000 folks that would tackle this issue and at an equivalent time be affordable to the govt and concrete poor.

Previous efforts by the government to supply low-cost urban housing in India were aimed at supplying ready-built units. Still, it took too long to construct a complete house, and it came precious for the low- income group and also ate up too numerous coffers.

A rectilinear point of 86 hectares was designed to accommodate over 6500 residences, largely for the Weaker Profitable Section. This was an integrated approach for ‘a sustainable society’ where the combination of various economic levels of society could stick together .

Aranya Low-Cost Housing accommodates over 80,000 individuals through a system of homes, courtyards, and a labyrinth of internal pathways. The community comprises over 6,500 residences, amongst six sectors–each of which features a variety of housing options, from modest one-room units to spacious houses, to accommodate a range of incomes.

Balkrishna Doshi says, “they are not houses but homes where a happy community lives. That is what finally matters. It seems I should take an oath and commit it to memory for my lifetime: to supply rock bottom class with the right dwelling.”

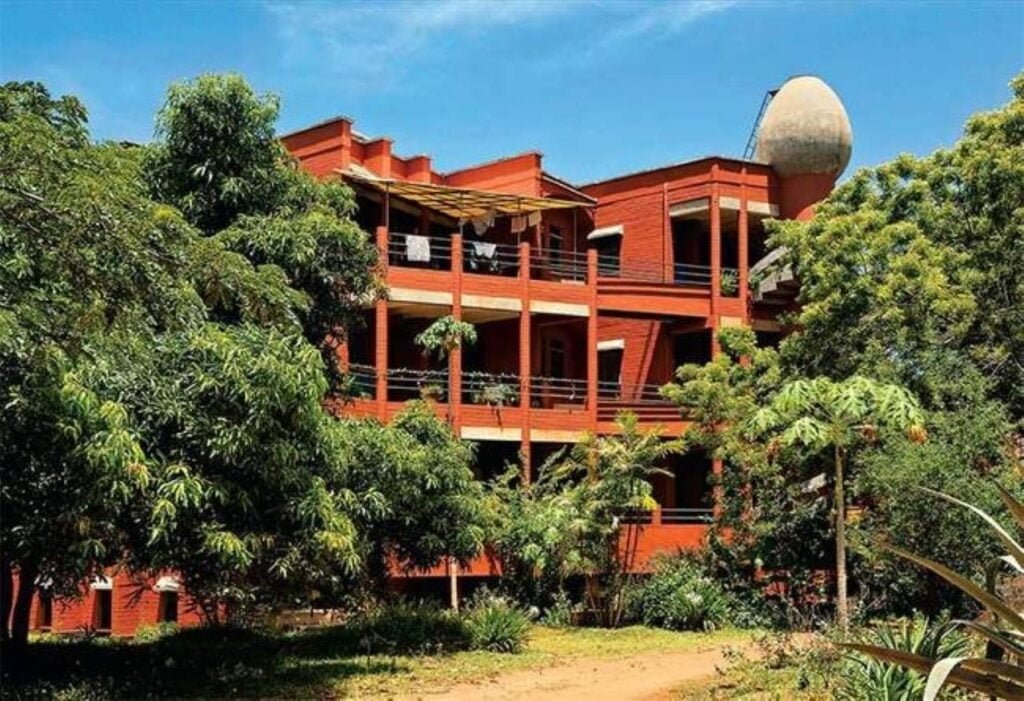

Vikas Community Housing, Auroville, Tamil Nadu

Vikas community housing built in 19992 till 1998 in Auroville is a type of incremental housing. In this community housing, the community kitchen was built first, then subsequently residential apartments. The creation of this community was supported the spirited lifestyle of Auroville’s ideal of life.

Environmentally appropriate materials, design, and methodologies are wont to build these environmentally conscious dwellings. Renewable energy also as advanced water management techniques, are incorporated into the project. Appropriate design and self-build methods have both been used in the project and funding of the project has mostly come from individuals who want to live there.

The project was inbuilt three phases: the primary was to create the collective kitchen and a block of 4 apartments, the second phase was for a block of six apartments, and therefore the third phase comprised a block of thirteen apartments on four floors plus some individual houses. Woodless construction methods have been used with 5 percent cement stabilization for compressed earth blocks, rammed earth, and other earth-based technologies.

M.A.C Community Centre, Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu

The project originates from a partnership between Made in Earth and Terre des Hommes Core Trust, an ONG which takes care of youngsters in trouble (abandoned or orphans, disabled or abused), giving them a home, an education, and possibly following till thru the utilization age.

MiE and TdH share a technique made from small interventions to be spread everywhere in the region, so to make a network capable to multiply the positive effects of everyone.

The Community Hall (now M.A.C.) of Tiruvannamalai is one of the knots of this network. It’s an area where all the NGO community (children, parents, tutors) can gather together and also meet the opposite citizens of Tiruvannamalai. A place where the ONG opens itself to the entire town and tell its story: the building had to contain a permanent exhibition of the NGO evolution through the years, and occasionally guests’ public events.

The design approach of Made in Earth is relatively realistic and (conceivably) not tone-referential, which means trying not to put any pre-constituted idea this helps, for case, in the selection of the materials, that are chosen to keep in mind their cost and real vacuity, rather than a particular image of fantastic architecture.

The M.A.C. building (walls, pillars, roof) is simply made from one material, concrete. All blocks are handmade, with an assembling scheme that makes a sort of pattern while varying the wall density; the blocks are used also as a neighbourhood of the formwork for the pillars casting, then to quicken the method. But in the end, it reminds the & fashion, the great perforated defences of the traditional Indian architecture.

Valpoi Bus stand, Valpoi, Goa

This building was a response to a proposal by the government of Goa to construct a multi-utility public building in Valpoi. It had to include a Machine Stand, a Community Hall, and a Children’s Playground with a jogging track. The Building complex is required to be maintenance free and on a low budget, with all units independent in their operations, function, and administration.

Valpoi being nestled within the magnificent Western Ghats is usually frequented by a military of hovering clouds that carry with them an armor of lightning and thunder. The design tries to capture this wonder of nature. Valpoi faces a periodic downfall of 200 inches from June to October. The design evolved in response to the brief and, therefore, the climate. The plan thus is compact, less porous, yet open in its station, well breezy, and adequately lit.

The Community Hall

Through a maze of laterite wall passages, you reach the Community Hall, drinking you with its hugeness and silence. The scenery is minimum, the lighting cleverly restrained and the space wonderfully sublime.

The Children Park

Children’s Park, at the west end of the site, is a contrast in its attitude. The colors disaccord against themselves, fabricating purposeful chaos. The play outfit respects the chaos as “Child’s Play”. A well-leveled and paved walkway meanders around the play area and the estate, which when walked on unexpectedly covers half a kilometer, qualifying it to be Joggers Park too.

Shaam-e-Sarhad Village Resort, Hodka, Gujrat

Shaam-E-Sarhad village resort is an eco-resort inbuilt a Kutchi village-style setting using locally sourced materials and crafts of the region. A pastoral community in the grasslands of Banni, considered ‘backward’, built this resort to bring modern societies into their lives so that the community may sensitize them on the qualities of ‘living lightly on the land.

The resort, erected, run, and managed by the pastorals, is used as advocacy to espouse their values, which insist that commons make better economics than privatization; their knowledge systems in sustainable living, where it’s delicate to separate profession from custom and art.

Jetavan Centre, Sakharwadi, Maharashtra

The institute was conceptualized as a spiritual & skill development center for the native Baudh Ambedkar Buddhist community. The accreditation of Jetavana is to give a spiritual anchor for the practice of Buddhist allowed through contemplation and yoga while also conducting training and skill development for members of the community.

With the mandate of not harming one tree on-site, the sizable program was broken up into 6 buildings each situated in gaps between the heavy planting. Through the planning process, two courtyards emerged as links suturing these buildings into a standard identity.

The approach to the Jetavan project attempts to extend the idea of the regional paradigm whilst separating it from the pervasive ‘image’ of what defines the local. The construction process also sets out an approach that appears to develop construction techniques that supported local materiality, not necessarily used natively but appropriate for its context.

Narayantala Thakurdalan, Bansberia, West Bengal

Narayantala Thakurdalan, a concrete Hindu temple with a glazed corner that opens onto the road in Bansberia, West Bengal.

If all the glass doors are opened, the entire external corner is often opened to show the inside and therefore the plinth into a bigger haunt .

“This place of worship played a special role in each person’s lifestyle and this provided cues for the planning of the space,” added the studio.

The porous facade allows people to possess a visible reference to the shrine even in passant while maintaining a fanatical space for daily worship at a small remove from the bustling intersection.

The temple was completed in six months, from design to consummation. It hosted the community’s Durga Puja fests in October 2018. While the final outgrowth was well appreciated by the community, it must be noted that some feedback was entered where it was felt that the former structure, having had a long-term association with the members, sounded more ‘at home’ than the new bone.

Artists Village, Belapur, Mumbai

The design is characterized by the scale of spaces in terms of private and collaborative areas. Then 8 units partake in a common yard and three of these groups form a module with an ample quantum of green spaces to feed to the different requirements of the townies.

It is also an illustration of the incremental casing. The informal character of roads and common collaborative spaces give an identity that allowed enhanced relations that saved the substance of the village.