Table of Contents

Introduction to Vernacular Architecture

Vernacular architecture is a style of architecture that is designed and built for the needs of people, with locally available materials, reflecting upon the culture of the place. Vernacular architecture is specific to a region and climate. In theory, a vernacular building is built without the guidance of a professional, like an architect. Thus, vernacular architecture is cost-effective, climate-responsive, modest, sustainable, and a reflection of the culture of the place.

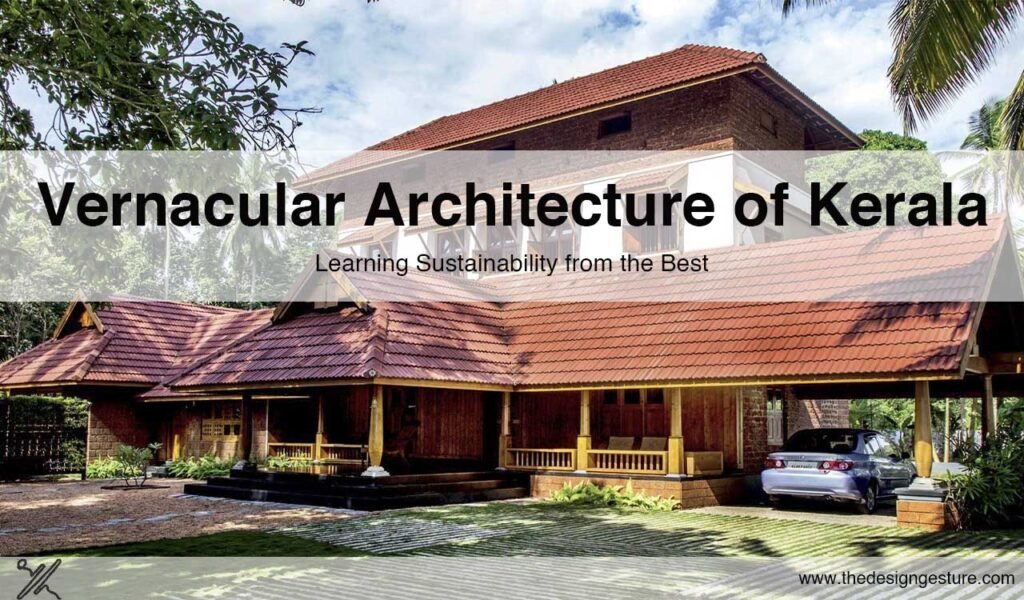

Introduction to Kerala and its Architecture

Kerala is the twenty-fifth largest state in India, in the area surrounded by Karnataka on the northeast, Tamil Nadu on the east, and the Arabian Sea on the west. With a coastline of around 600km of the Arabian sea, Kerala is known for its spectacular flora and fauna, backwaters, and respect for its culture.

Kerala prides itself for being the flag bearer for not just how a culture can respect its past, but also march forward with growth & progress as well. Kerala’s vernacular architecture, which is still heavily practiced throughout Kerala and some of south India, is one such inspiration for all. It is in striking contrast with the Dravidian Architecture followed in other parts of South India and is strongly influenced by Indian Vedic architectural science (Vastu Shastra).

History and Origin

Kerala gets its indigenous style of architecture from all climatic, geographical, and historical factors.

Favored by generous rains because of monsoon and bright sun, this land is lush green with foliage and rich in beast life. In the uneven terrain of this region, mortal habitation is distributed thickly in the rich low- lands and sparsely towards the hostile mounds. Heavy rains have brought in presence of large water bodies in form of lakes, gutters, backwoods, and lagoons. The climatic factors, therefore, made its significant benefactions in developing the architecture style, to fight the wettest climatic conditions coupled with heavy moisture and harsh tropical summers.

Geographically, Kerala is a narrow strip of land lying in between the seacoast of peninsular India and confined between the towering Western Ghats on its east and the vast Arabian ocean on its west.

History also played its benefactions on the Kerala architecture. The towering Western Ghats on its east have successfully averted influences of bordering Tamil countries into present-day Kerala in after times. While the Western Ghats insulated Kerala to a lesser extent from Indian conglomerates, the exposure of the Arabian ocean on its east brought in close connections between the ancient people of Kerala with major maritime societies like Egyptians, Romans, Arabs, and so on. Kerala’s rich spice polish brought it a center of global maritime trade until the ultramodern ages, helping several transnational powers to laboriously engage with Kerala as trading mates. This helped in bringing in influences of these civilizations into Kerala’s architecture.

Different types of Kerala Architecture

The architecture of Kerala is divided into two parts, Nalukettu and Ettukettu.

Nālukettu is the home of generations of joint family kinfolk or Tharavadu, where many generations of a matrilineal family lived. These types of structures are observed in the Indian state of Kerala. The traditional architecture of Kerala is a rectangular structure where four blocks are joined with a central, open to the sky courtyard.

The four halls on each side are named Vadakkini (northern block), Padinjattini (western block), Kizhakkini (eastern block), and Thekkini (southern block). The architecture was especially provisioned to large families of the traditional tharavadu, to live under one roof and enjoy the commonly owned facilities and services of the marumakkathayam homestead.

Ettukettu, which is eight halls with two central yards) or Pathinarukettu, which is sixteen halls with four central yards, is the further elaborate forms of the same architecture. Every structure faces the sun, and in some well-conditioned designed nalukettu, there’s excellent ventilation as well. Temperatures, indeed in the heat of summer, are markedly lower within the nalukettu.

Elements of Nalukettu and Ettukettu

Padippura

It’s a structure containing a door, forming part of the boundary wall for the house with a tiled roof on top. It’s the formal entry to the site with the house.

Poomukham

It’s the porch of the house led by steps. Traditionally, it has a pitch-tiled roof with pillars supporting the same.

Chuttu gallery

In Kerala architecture, the poomukham is accompanied by an open passage, the chuttu gallery, which leads to either side of the house surrounding it.

Charupadi

Along the chuttu gallery and the poomukham are traditionally sculpted, rustic, wooden, or cement benches. These benches are called charupadi.

Ambal Kulam

Nearly every Nalukettu has its own Kulam or Pond for bathing of its members. At the end of Chuttu verandah, there is a small pond constructed with debris on sides where lotus or Ambal is planted. The water bodies are maintained to maintain energy flow inside.

Nadumuttam

A typical Nadumuttom of Kerala Nalukettu is a courtyard placed at the prime center of the Nalukettu. This is surrounded by an open corridor square-shaped, in the exact middle of the house dividing the house into its four sides.

Key Features of Vernacular Architecture of Kerala

Orientation and Planning

Kerala experiences a hot and humid climate and hence the orientation of the building becomes one of the crucial aspects of planning.

The building should face the direction of the prevailing winds rather than the sun. This helps in maintaining cross ventilation in a humid climate. Houses preferably face East direction according to the direction of prevailing winds.

Cross ventilation

The juxtaposition of open-and-closed spaces in a way to allows a continuous flow of air.

Being in a tropical climate, cross ventilation plays an important role in creating comfortable spaces. The presence of high moisture content in hot air causes discomfort for the user.

Courtyard spaces are extensively used in houses of Kerala of all scales. It helps in achieving passive cooling and reduces the dependence on HVAC systems. It also helps to induce continuous air movement.

Openings in walls facing each other and internal partitions help in increasing cross-ventilation. Using vertical louvers and large window shutters helps to reduce thermal discomfort with ample daylight.

Solar Shading

The temperature in Kerala can rise to up to 40 degrees Celsius in summers. Therefore, sun shading strategies and elements become vital.

Traditional buildings in Kerala have an internal and external verandah. The external verandah acts as buffer space to reduce direct exposure to sunlight, whereas the internal verandah allows light to enter the building via a courtyard.

The east and west façade should be least exposed to the sun to prevent late afternoon and early morning heat. One way is to have dense tree plantations around these façades.

Overhangs, louvers, canopies, and so on are used for shading. Shading devices for doors and windows are also used to avoid solar heat gain.

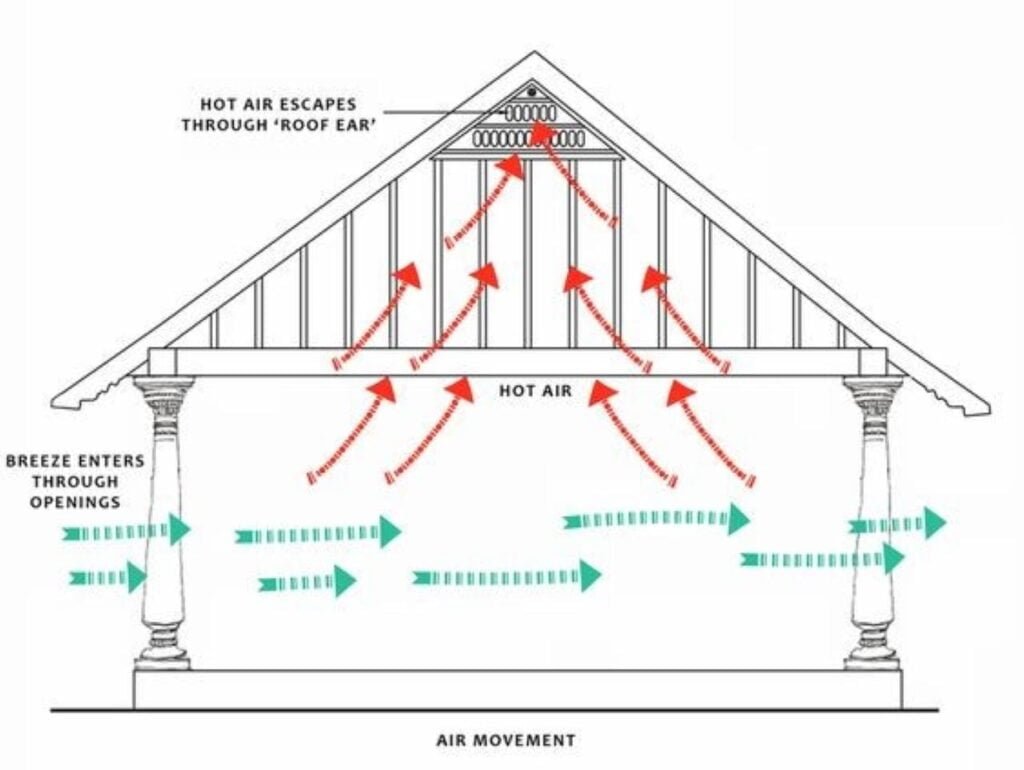

Roof Insulation

The most distinctive visual form of Kerala’s architecture is the high, steep sloping roof with eaves constructed to shade the walls of the house and to repel the heavy thunderstorm, typically laid with tiles or thatch, and supported on a roof framework made of hardwood and timber. Structurally, the roof frame is supported on the pillars standing on a raised platform from the ground, for protection against moistness and insects in the tropical climate. Many times, the walls are also made of timber, locally available in Kerala.

Gable windows were introduced at either end of the roof to maximize attic ventilation of the room when the ceiling was incorporated for these spaces. Most structures of Kerala appear to be low height visually, because of high, steep sloping of roofs, which cover walls from rains and direct sunshine.

Prevention from Rain

Kerala receives heavy rainfall for a significant part of the year which requires effective solutions to endure the extreme climatic conditions.

Buildings should be placed at a high plinth to restrict water from entering inside. Sloping roof should be provided to avoid the accumulation of rainwater on the surfaces.

Commonly Used Materials

Kerala architecture uses local materials that are locally available and also sustainable. Some of the commonly used building materials in the Kerala area are bamboo, earth, lime, timber, leaves, and so on.

Laterite

Laterite is a hardened earth layer formed because of the weathering action of acid jewels. It is dug out from the earth and its compressive strength can be significantly higher than that of burnt clay bricks. It is non-porous and has poor water retention capacity. It is found 3 to 15 meters below the ground. The top one to two meters is soft, and the bottom merges with the clay layer. Laterite can be called the “Blessing of Kerala” since 80 percent of the state is covered with it. In Kerala, the foundations were erected with laterite blocks.

Laterite has been extensively used for constructing the superstructure. Using burnt bricks for construction was rare, except with a few palaces. Currently, the laterite blocks can be machine cut as well. The advantage of these machine-cut blocks is that they have much higher compressive strength. The disadvantage is that these have to be transported over a long distance, ergo the process involves further energy.

Lime

Lime, which was obtained from shells, was burnt in kilns and used as mortar in structures in Kerala. It was produced by beating it round with a stiff bristle encounter, after adding water. It was beaten with a special rustic tool in tanks specifically made for this purpose. This process helped to increase its strength and plasticity, reducing the amount of water to be added. This is beneficial as the strength of lime further improves when lower water is used, and when it’s air-dried. Many organic details were also added to increase the strength of the lime, hence the mortar.

In theory, it is believed that lime has a lot of disadvantages like slow setting, not having enough strength, and so on. But, in contrast, lime is significantly sustainable as a binding material, as various studies show that it is much lower energy-consuming when compared with cement. Cement is a high energy-consuming material with limestone as one of the main constituents for its manufacture. When cement is used as mortar in a wall, the bricks cannot be recovered for play, if the structure is demolished latterly. If lime is used, the bricks can be reused, which eventually makes lime mortar more sustainable.

Granite

Granite is the most common stone used for construction in Kerala. Traditional Kerala houses use a granite slab below the ground to avoid the risk of dampness. Whereas thatch or clay tiles on the sloped roof, keep it dry.

The state does not have deposits of limestone or sandstone. Granite is a hard stone and is used in the foundations. It has been infrequently used for the superstructure until lately.

In the olden days, it was a locally available material, but now big quarries have come up in the western ghats, many of whom are present in vulnerable and fragile areas. Granite that is being excavated from these places is not sustainable, because of the adverse impact it causes on our terrain as landslides and other natural disasters.

Timber

Timber is one of the most used structural materials in Kerala. It was extensively available in many kinds and with high durability as well. Teak, jack wood, Anjili wood, and Thembavu were some of the commonly used types of timber.

Structures with timber walls were constructed in Travancore till about 100 years ago. The vernacular architecture of Kerala considerably uses timber for walls, doors, windows, intermediate floors, and roofs.

The biggest advantage of timber is that by using them in our buildings, the carbon gets locked. Trees are the only things that can convert carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into oxygen. If timber is allowed to decay or used as firewood, then the carbon is released back into the atmosphere, completing the carbon cycle.

Every timber that we use in our structures needs not be sustainable. However, also it is less sustainable if the source of the timber is from cutting down virgin forests.

Earth/Mud

In earlier times, several large structures were constructed using earth or mud. The sun-dried mud bricks may be used for the alternate story of a two-story structure, with the ground bottom made of laterite. They may also be used for the less important corridor of structures. Using earth blocks (without ramming or sun-dried bricks) was popular among the poorer sections of society.

Many structures constructed with laterite also use earth as mortar to save the cost of construction. The general print of the public is that a structure with earth blocks is sustainable. But most times, it need not be true.

The cost of the superstructure of a structure is only 15-20 percent of the overall cost of construction, meaning the rest of the structural units need not be sustainable at all. When the earth from the structure point is used, it becomes very sustainable. But if the material has to be transported over a distance, also the embodied energy will go over, reducing the sustainability factor. Strengthening of earth blocks by cement will also reduce the sustainability aspect. If interlocking earth blocks are used, also the sustainable character will be more since no cement mortar is involved.

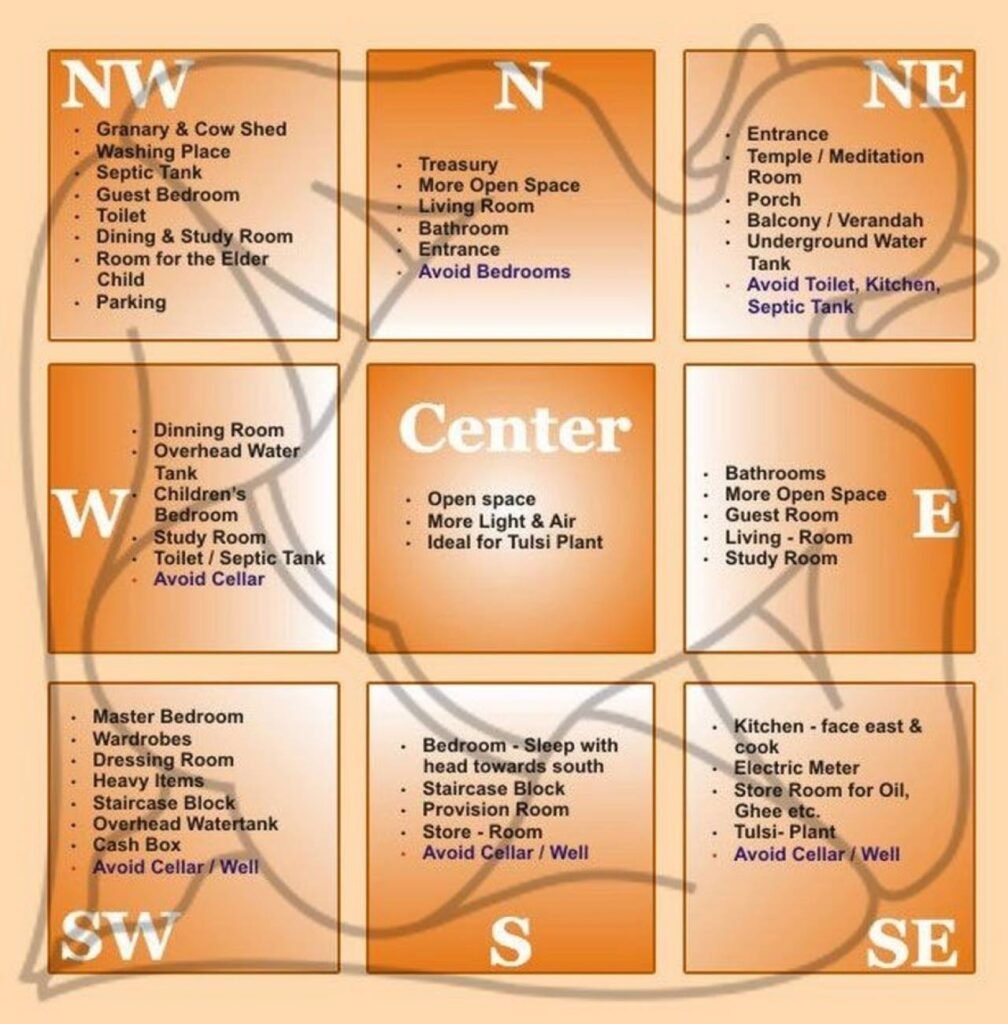

Influence of Vastu Shastra

One can notice the strong influence of Vastu shastra’s study on the architecture of Kerala. The basic underlying belief is that every structure erected on earth has its own life, with a soul and personality which is shaped by its surroundings. The most important wisdom which Kerala has developed purely indigenously is Thachu-Shastra (Science of Carpentry) as the easy vacuity of timber and its heavy use of it.

From cattle sheds to trees, everything used to be planned and laid according to the ancient texts of shastra.

In traditional houses, the kitchen is strategically placed in the northeast corner as the prevailing winds blow from the southwest direction. These houses have pitched roofs and if the roof catches fire at any point, it will be blown away by the prevailing winds. A well would also be constructed close to it. In a house with a courtyard, the main living area is always in the southwest part, away from the fireplace. The puja room of the house is placed in the northeast corner and the idols face either east or west direction.

In two to three-storied houses of Noth Kerala, the northeast part is usually a single storey because of the kitchen. The bedrooms are present upstairs in the southwest direction.

Conclusion

There has been a rapid change in the architectural fraternity in the past two decades. The new trend has been fast-paced racing towards quantity over quality. Using craftsmen has declined considerably.

Therefore, to get out of this present crisis, an architecture typology, like the vernacular architecture of Kerala, that suits the environment, climate, and the people, should be developed. A blend of vernacular architecture with modern needs seems an appropriate solution.