Architecture is unlike most other forms of art. A writer begins by writing words on a page that will eventually form a book or a play. A dancer’s body moves to become the dance. An artist creates the ultimate work of art by drawing or painting it.

Architects, on the other hand, do not create architecture. Architects create a portrayal of architecture that is abstract. As a result, it’s critical to comprehend what this entails. Architects, unlike other creative forms, do not have time to learn how to make architecture by physically making it. It is too large, will take a long time to complete, and will require many people and a large sum of money. Instead, we need to figure out how to depict the ultimate design so that we can better understand, test, and convey what it will look like.

Table of Contents

Abstraction

Abstraction is the process of limiting something to a collection of fundamental tenets by eliminating or removing characteristics. Abstraction is the process of capturing and concealing data or information, leaving only what is necessary to communicate your message.

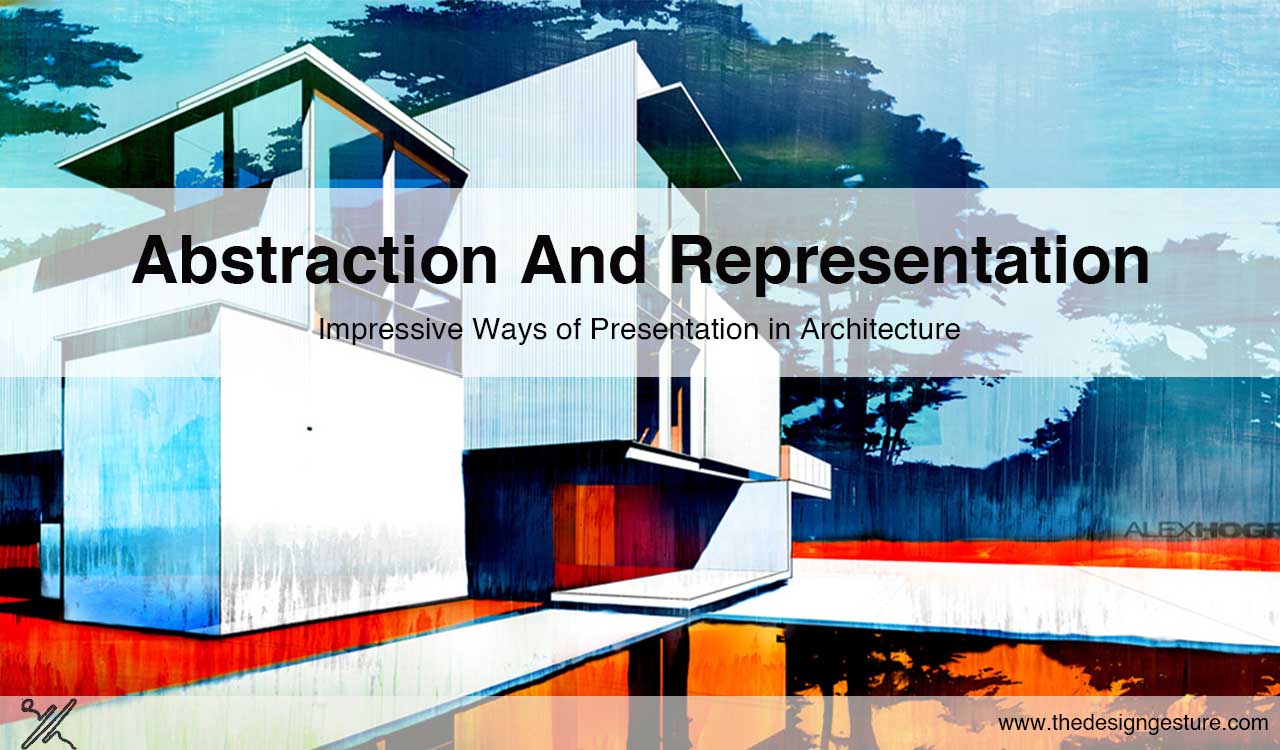

Because it is not the final piece of architecture, all architectural communication is a form of abstraction and representation. It’s a mock-up of what that piece of architecture could look like. Each piece of communication an architect creates serves a certain purpose and conveys a specific message.

Architectural Communication Styles

The act of generating meaning among groups through the use of sufficiently understood and agreed-upon signs, symbols, and customs is known as communication.

Communication is used in architecture in a variety of ways throughout the design process, including:

Written documents

Letters, reports, emails, meeting minutes, contracts, and schedules are examples of papers that can be used to document the process, requirements, conversations, ideas, approvals, and changes to a project.

Sketches

Sketches are an architect’s first foray into the design process, a way of watching and exploring the progress of a project, or even representing solutions for it. One can better comprehend how a specific design move echoes throughout an entire work by looking at an architect’s sketches.

Mapping

The act of making a drawing, painting, or diagram that depicts something that already exists.

Orthographic Drawings of Abstraction

Two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional objects. The majority of orthographic drawings are made up of a set or suite of drawings that portray each side (i.e., top, bottom, 4 x sides) and should be read together. One type of orthographic drawing is house plans.

Collage

A work of art or visual representation created by combining several forms and materials, such as paper, fabric, or wood, to generate a new composition.

Modern visualization methods have produced outstanding illustrations, which are now essential in architectural displays. Instead of diving into “digital post-collage” and unlocking new realms of design, some people prefer to investigate items in novel ways.

(ab)Normal is a graphic patchwork that expresses design, scenography, illustration, architectures, and social utopias of a culture that revolves mainly around the Internet, gaming, and religion. It was created as an experiment in visual tales. The iconographic images, which are primarily concerned with architectural representation, investigate all the possibilities of rendering, deconstructing, and reassembling photo-realism using various hierarchies.

Models

The final piece of architecture as a real, three-dimensional representation. Typically, these are created on a considerably smaller scale than the final product. The final piece of architecture as a computerized, three-dimensional depiction. These are normally modelled at life size but can only be viewed at a reduced size on a computer screen or printed piece of paper.

Photography

Photographing something as a record or representation.

Constructed form

People can experience three-dimensionally in real life the final piece of architecture.

The Human Figure’s Potential in Architectural Representation

Understanding scale in graphics, hyper-realistic renderings, collages, and three-dimensional representations requires an understanding of the human body. However, it frequently appears to be one of the last things to be included when it should be a deliberate and integral part of the project. These figures serve as a clear and straightforward indicator of a space’s proportions in orthogonal architectural representations.

The comparison of architecture to our bodies becomes almost instinctive due to its familiarity. We correlate our body’s dimensions with those of the depicted figures, allowing us to naturally comprehend space’s dimensions. In terms of perspective, the figures take on a new role of providing depth to the depiction by including a third dimension.

The usage of the human figure allows us to convey thoughts about how space is conceptualized; it also highlights contents, shows tasks, suggested uses, functional qualities, and even user profiles. The figures thus function as polysemic elements that, besides scale and depth, employ the architectural representation’s communicative nature to convey other notions.

Evolution of representation in Architecture

The concept of space had evolved from a metaphysical concept in the late nineteenth century, and Hildebrand, Schmarsow, and Riegl saw it as an aesthetic concept. The diagram appeared at the end of the 1920s, signaling a transition to a more scientific approach to design that didn’t break from an eclectic design based on a past proper style, but rather one prompted by a complex of design circumstances.

At architectural schools, form, materials, and space were now linked to human perception studies, and traditional analytical architecture classes were replaced by new introductory courses in which new students learned about perception and language. The widespread availability of photography, cinema, and home television by the mid-century ushered in a new image culture. Photomontage and collage techniques were offered as novel communication tools in companies and design schools.

CAD Evolution

Beginning in the early 1960s, representation became associated with new computer technologies. Ivan Sutherland created the Sketchpad graphic interface technology in 1963, which allowed users to create virtual drawings using a digital pen10.

Computer-aided design (CAD) systems gradually gained popularity over the next decade, culminating in the release of AutoCad11 in the 1980s. CAD drawings were usually powerful 2D drawing tools, only permitting 3D construction and 3D rendering views in other computer environments that operated concurrently to the 2D one, despite the technical innovation approach.

Building Information Modelling (BIM)

However, at the end of the 1980s, a new three-dimensional object representation technology called Building Information Modelling (BIM)12 emerged. Its key breakthrough, while still based on Monge’s method, was the ability to incorporate full building information and display the depicted object in virtual three dimensions, viewable from any point and angle. We moved on from the prior CAD programme and began creating three-dimensional operative virtual models with a high level of detail (e.g., Autodesk Revit13). It was now feasible to construct an architectural project with a good understanding of its three-dimensional shape and immediately discover, while still in the design process, complex scenarios that were previously difficult to forecast and required a strong mental effort of elements’ combination.

Immersive Digital, Interactive, and Augmented Environments in Virtual Reality

Traditional representation systems are no longer adequate to translate and communicate the complexity inherent to new geometry spaces14, where the plans that define them abandon their usual orthogonal nature and become a game of multiple relationships that can eventually lead to a single connected surface with the ability to adopt infinite variations.

As architecture representation progressed into the realms of virtual reality (VR) and immersive digital environments (IDE), new and more significant capacities in understanding virtual worlds of architecture emerged. Unlike the aforementioned approximation approaches of reality, such as collage, photomontage, or rendering, immersive virtual reality technology allowed for the creation of not only visual products of created locations but also authentic intense experiences of those spaces.

When someone needs an architect to create his castle, he can no longer rely on traditional plans, sections, and elevations, nor on printed photomontage or virtual walkthroughs on a computer screen. He’ll be able to stand in his yet-to-be-built living room, walk to the kitchen, and visit the bedrooms, gaining a lot better knowledge of those places and if they’re genuine as he expects them to be. Indeed, having access to this type of technology, the most significant differences between the virtual space representation and its eventual physical construction are mostly determined by the amount of development and visual complexity of the virtual world.

Future Developments

There is now a widespread belief that the line between reality and the virtual environment will gradually blur. This vision is the consequence of a sense of gradual internalisation of a variety of immaterial ideals, which liberates people from their previous bounds of corporeality and sense of place. As a result of the widespread adoption of new communication technologies that allow individuals to transcend traditional boundaries. With overlapping images, we become acquainted with the immediate, residing the intangible. As a result, we can envision a new type of creature.

Architecture in accordance with modern values: a far more homogenous, transparent, ephemeral, a changeable and immaterial place that calls into question the traditional material substance and the eternal architectural characteristics.

With a growing sense of urgency, architecture students approach the issue of representation. There is a lot to learn, and it must be done quickly. Plans, it turns out, are more than just a bunch of rooms and halls on a paper; they’re a way of thinking about buildings. Perspectives are more difficult to understand, yet they are possibly less esoteric.

Then there are the many instruments, drawing media, modelling materials, software, and digitally mediated apparatuses to learn about. Even the most basic aspects of architectural representation show that mastering its tools and procedures requires more than just skill.

It is obvious from the start that the hand and mind interact in intricate ways in representation. Architects use representation to think, create, and communicate, yet traditional methods impose their own agendas. Traditions are passed down, demands are made, motives are shifted, and communication is shaped.

Architects, predictably, dispute and evade these strategies while still using them. So, learning about representation entails more than just gaining a set of useful studio skills; it also entails realizing that representation is the primary task of architecture and one of its most tough challenges—one that takes more than a few weeks to master.