Table of Contents

Introduction

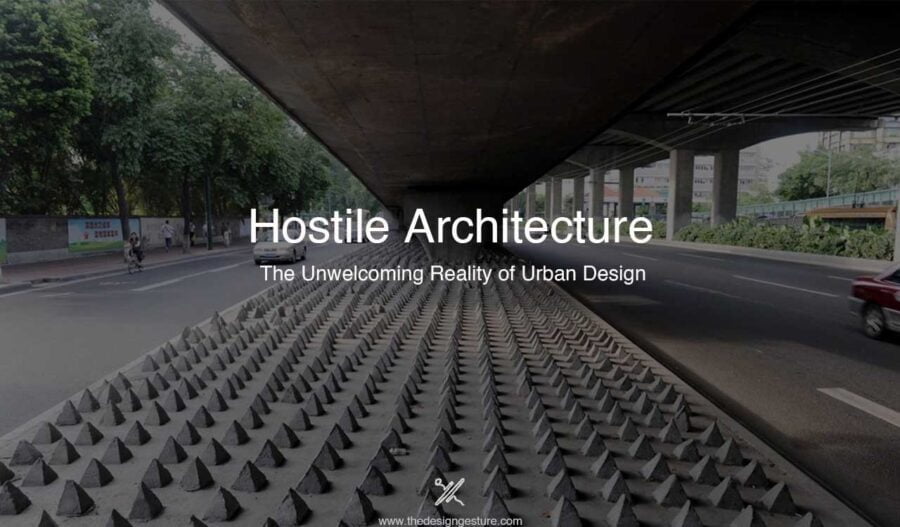

Hostile architecture is the antagonist of the public domain as it seeks to destroy inclusivity and create boundaries for marginalized groups. Communal spaces in the built environment are a crucial aspect of inclusive urban planning, as architecture brings aesthetics, performance, and the ability to nurture a community. Hostile architecture utilizes modified structures to discourage certain frowned-upon behaviors, such as loitering, skateboarding, or sleeping in public. This controversial style of architecture has detrimental impacts on society and prompts the discussion of its ethical implications.

Defining Hostile Architecture

The main aim of hostile architecture or defensive architecture is to regulate public behavior. This public control is often to the detriment of individuals seeking refuge or temporary rest in these spaces. Hostile architecture employs specific structural elements to exclude certain groups of people of behaviors in public environments such as public restrooms or parks. These structural components are harmful, such as metal spikes on floors, titled seats, armrests, and dividers on benches to prevent lying down, as well as rough-textured surfaces to prevent skateboarding.

In British Columbia, Canada, blue lights are installed in public washrooms to prevent drug use. Blue light makes it difficult for the addict to locate a vein to inject the drug. Yet, this does not hinder the individual to inject the drug and cause infection. This tactic of hostile architecture causes more harm, obscures visibility, and creates challenges in cleaning bodily fluids.

Intentions of Hostile Architecture

The presence of hostile architecture has ignited a debate on the ethics concerning architecture. People in support of hostile architecture suggest that by deterring undesirable actions such as loitering or sleeping in public, the general communal domain will become more appealing to law-abiding citizens, leading to low crime rates and vandalism costs. Defensive structures serve as an important tool to enforce order, protect resources, and promote community safety, according to hostile architecture adherents. Hostile architecture contends that it will prevent spaces from being overtaken by drug users, homeless people, and other perceived deviants.

On the other hand, critics contest these claims by stating that hostile architecture exhibits a broader dilemma. The use of defensive structures perpetuates exclusion, prejudice, and the negligence of effective city planning. The disregard for the needs of both vulnerable and marginalized communities is addressed by the extreme use of these defensive structures. Hostile architecture fails to highlight the underlying reasons behind these societal problems and the lack of understanding of city planning. The ethical discussion surrounding hostile architecture is centered on finding the balance between public safety and encouraging inclusivity, urging a shift towards people-centric and compassionate design principles.

The Impact on Society

Hostile architecture prevents access to public spaces which raises moral concerns about its role in urban planning. Defensive architecture fixates on the aesthetics and the benefits of property owners. This breeds an environment of distrust and disdain among the community. Hostile architecture conjures spaces of discrimination against certain communities such as the homeless, youth, and people with disabilities, rather than developing a welcoming built environment.

Due to the lack of concern with community-centered design, hostile architecture can harm the mental well-being of people. When individuals are constantly confronted with inhospitable surroundings, they may feel alienated and unworthy. For example, metal spikes on surfaces that are meant for stopping skateboarding can inadvertently inhibit people in wheelchairs from accessing those spaces as well. The inability to find comfort in public spaces can intensify existing social inequalities and reinforce the cycle of poverty and exclusion.

The Invisible Barrier of Hostile Architecture

There are obvious examples of hostile architecture, such as metal spikes on ledges, but there are more subtle and equally effective designs that deter certain behaviors. A notable example is implementing armrests on benches that may appear harmless initially, but they intend to discourage individuals from lying or resting on the benches. Similarly, deploying high-frequency sounds that can only be heard by younger individuals is an effort to discourage lingering by specifically targeting certain age demographics. By employing such discreet measures, advocates of hostile architecture hope to achieve their objectives without drawing too much attention or public criticism.

Despite this, the growing concern and public outcry have revealed the true intent, compelling urban planners to reassess the morals and long-term effects of hostile architecture.

The Criminalization of Poverty and Homelessness

The creation of uninviting environments meant for the public makes it difficult for homeless individuals to access. Hence, hostile architecture contributes to the criminalization of poverty and homelessness. Marginalized groups are pushed to the outskirts of society as hostile architecture denies basic human rights, such as the right to rest and shelter. Rather than focusing on the root causes of homelessness and providing services, city planners choose detrimental actions that further isolate and stigmatize vulnerable people.

Hostile architecture perpetuates the notion that poverty and homelessness are individual failings rather than systemic issues that demand compassionate and comprehensive solutions. As a result, those in need are pushed into hidden corners, away from public view, exacerbating their already challenging circumstances.

The Role of Corporate Interests

Hostile architecture can be attributed to the influence of corporate interests on public spaces. Shopping centers, for instance, might install uncomfortable seating arrangements or time water sprinklers to prevent loitering and encourage continuous patronage. Individuals are entitled to protect their properties but it is vital to consider if business is more important than the well-being of the general public. Open areas in cities fulfill various roles, such as gathering spots, cultural hubs, and platforms for community participation. However, when these spaces are designed to display consumerism over communal experiences, it can lead to a loss of public ownership and a shift towards a society focused solely on consumption.

The Global Movement Against Hostile Architecture

Over the past decade, a surging global movement against hostile architecture has been developing. Architects, artists, activists, and concerned citizens of society have united to combat the use of these detrimental structures and demand more interconnection and compassion in urban planning. Due to public pressure, some cities have taken steps to remove hostile architecture from their communal spaces. Cities like Melbourne, Australia, have implemented design guidelines for more people-friendly spaces. Additionally, urban environments are being reclaimed with community-led grassroots initiatives. These design projects allow for accessibility, safety, and comfort for all residents.

The Call for Inclusive Design

Many architects, urban planners, and activists reject hostile architecture and support the shift toward inclusive design principles. These principles seek to create a more accepting public space that accommodates the diverse needs of all inhabitants regardless of socio-economic status, age, or ability. Instead of implementing hostile architecture, advocates suggest a people-centric approach that encourages collaboration, and community building. Diverse and inclusive design can take multiple forms, such as the following:

Adaptable and Temporary Shelters

In the face of the global homelessness crisis, compassionate architecture becomes crucial to address the needs of vulnerable populations. Adaptable benches with roofs or pod housing offer a promising solution as a temporary shelter, protecting from the elements and a sense of safety. The Raincity Bench program located in Vancouver, Canada has introduced benches that can be modified into sheltered spaces for the homeless, offering a practical and humane approach to public space design.

Green spaces

As urban expansion grows, green spaces become alarmingly scarce, limiting opportunities for human interaction with nature. Green spaces are vital for fostering social connections and enhancing well-being. Inclusive design principles call for the inclusion of parks and green scenery within urban landscapes. In Singapore, the Botanic Gardens create a lush and accessible urban garden that serves as a lively gathering spot. This social node allows for a strong sense of community and appreciation for nature.

Public art

Social engagement can be encouraged by public art and self-expression. Unfortunately, it is seen as vandalism in some societies. By allocating communal spaces for public art, cities can create a sense of ownership and pride among their residents. The Bristol City Council in the United Kingdom supports street art initiatives and designated areas for mural painting, transforming once dull and neglected spaces into colorful and vibrant expressions of community identity.

Skate parks

Skate parks develop safe environments for skateboarders to practice their skills and connect with other like-minded people. This social hub also serves as a recreational facility to explore new hobbies. A notable example is the Vans Off The Wall Skate Park in Huntington Beach, California. It caters to skateboarders and hosts various community events, workshops, enriching the urban experience for all.

The Role of Technology in Redefining Public Spaces

Innovative technology offers promising opportunities for re-imagining public spaces in a user-friendly manner and without resorting to hostile architecture. For instance, smart city initiatives leverage data and technology to optimize urban planning and create more community-centric environments. This data and technology serve as valuable devices for urban planners. The Internet of Things (IoT), enables the monitoring of shared spaces to adapt to the various needs of communities in real-time. For example, public seating areas could continuously adapt their configurations to accommodate different group sizes or to provide temporary shelter for the homeless during specific hours.

Conclusion

Hostile architecture is a controversial topic within the built environment. It stands as a powerful reminder of the ethical obligations of town planning and architectural design. Although many may argue it is necessary to maintain a peaceful societal structure, they are unwittingly prolonging social inequalities and the alienation of marginalized groups. It is imperative to transition into more inclusive design principles that accommodate the overall well-being of citizens. Urban planners can facilitate public spaces that cultivate human interaction, community-building, and empathy for a more vibrant and harmonious place for everyone to enjoy.

The community-centered design allows for the construction of diverse cities that create a shared sense of ownership, paving the way for a more equitable urban landscape. The path to achieving urban areas that are genuinely inclusive will present obstacles but, fundamentally, these places show the finest of human values. Reaching intersectionality in the public domain is achievable if those involved in the process – architects, town planners, decision-makers, and citizens – work together and talk meaningfully about the roles of people and design.