Table of Contents

Introduction

The goal of Architectural Ethnography is to learn about the future users of a design, such as a service. It’s a method for delving into the daily lives and experiences of the people for whom a design is being created. But before diving into the topic, it is very important to understand what ethnography means.

Understanding What Is Ethnography?

Ethnography is a field of anthropology that studies individual cultures methodically. Ethnography literally means “describing (graphing) the people,” but it also refers to the behavioral and tangible manifestations of culture, such as architecture. Ethnography investigates cultural phenomena from the perspective of the study’s subject. Ethnography is a sort of social research that entails observing and interpreting the conduct of participants in a given social environment, as well as the group members’ interpretations of that behavior.

Contemporary ethnography is almost only dependent on fieldwork, and it causes the anthropologist’s thorough absorption into the culture and daily lives of the people he is studying. In Social and Cultural Architecture, where the people are of primary value to space, ethnography becomes critical. This research can assist architects and designers in creating user-driven designs that enrich the rich cultural and socioeconomic values of their communities.

It may also be a descriptive study of a certain human culture or conducting one.

The ultimate purpose of social and cultural architecture classes is to enhance the design of buildings for people to live in. The following are some of the primary benefits of ethnography in architecture:

- It is possible to construct an exact depiction of behavioral patterns, which can help to create user-driven places.

- The study is conducted in a natural context, resulting in outcomes that are more direct, clear, and straightforward.

- It provides interpretations of the residents’ activities and behaviors that should be discovered by comprehensive research on what individuals do and why they do it.

- Explorations that focus on certain social phenomena and cultural features might be created.

Architectural ethnography was a concept-based strategy that Social Scientists used to research communities, culture, and society. Ethnography is divided into three categories: people, society, and culture.

In modern architecture, ethnography guarantees that ideas and innovations are valuable to the consumers. Firms nowadays are continuously looking for innovative methods to gain a competitive advantage. These businesses may use ethnography as a method to gain a deeper knowledge of and alignment with their customers’ values. As a result, ethnographic research and answers are becoming increasingly important in modern architecture.

With increasing competitiveness, user-responsive designs have become one of the primary necessities and a significant challenge to architects. “The user” is a fundamental theme in ethnographic studies in architecture; variables included in developing such a project include their basic requirements, cultural reactions, societal values, and many more. Given the quantity of study that goes into these projects, ethnography may be classified as an “emerging design strategy.”

Why do dwellings change from place to place?

The ultimate purpose of social and cultural architecture courses is to enhance building design for residents. To do this, the writers blend what anthropologists term the etic (outer) and emic (inner) points of view by assigning an ethnographic field study project to learn from building residents’ experiences. Photo-elicitation, an anthropological interview method that uses images to elicit residents’ points of view, is used to combine the etic and emic views.

Predicting what will work best for people causes a thorough grasp of their requirements. Focus groups and surveys have clear face validity, yet they consistently cannot give the insights that product development teams require. The reason for this is that these strategies demand users to forecast their future behavior, something most individuals are not good at. Another approach is to look at what individuals do rather than what they claim they do. This method is founded on a basic premise: previous behavior is the best predictor of future conduct. What individuals do is a better predictor of underlying user needs than what they say.

Rather than asking people what they want, the user researcher does design ethnography to learn why they want certain things. They use observation and interviews to answer questions like these:

- What are the goals that users are aiming to achieve?

- What are their favorite and least favorite dishes?

- What workarounds do they have?

- What obstacles will they encounter along the way?

A Simple Four-walled house vs a Home that celebrates Ethnography

Now let’s look at a simple example of two structures, one that celebrates local ethnography, and one that, well, doesn’t.

Studio KO, a French architecture firm created by architects Olivier Marty and Karl Fournier, designed the structure. The new facility, which covers over 4,000 m2 and is more than simply a museum, is on Rue Yves Saint Laurent, near to the iconic Jardin Majorelle. From the outside, the structure comprises cubic shapes ornamented with bricks that produce a pattern that resembles fabric threads. The interior is bright, velvety, and smooth, similar to the lining of a high-end couture jacket.

The structure, which is made of terracotta, concrete, and an earthen-colored terrazzo with Moroccan stone fragments, mixes in perfectly with its surroundings. The terracotta bricks that adorn the exterior are created from Moroccan soil and manufactured locally. The terrazzo that was used for the floor and facade is made using a combination of local stone and marble.

Designed by the Spanish architect, Alberto Campo Baeza, it is known as House Of The Infinite, a landscape architecture beach house design project which effectively conceals the two-story structure underneath a flat roof with geometry cutouts overlooking the shoreline of Cadiz, Spain.

Although ethnography is not crucial to architecture, it adds in that extra essential spice that makes you appreciate the structure better.

Examples of architecture built around principles of ethnography:

Musée Yves Saint Laurent Marrakech by Studio KO

Studio KO, a French architecture firm created by architects Olivier Marty and Karl Fournier, designed the structure. The new facility, which covers over 4,000 m2 and is more than simply a museum, is on Rue Yves Saint Laurent, near to the iconic Jardin Majorelle. From the outside, the structure comprises cubic shapes ornamented with bricks that produce a pattern that resembles fabric threads. The interior is bright, velvety, and smooth, similar to the lining of a high-end couture jacket.

The structure, which is made of terracotta, concrete, and an earthen-colored terrazzo with Moroccan stone fragments, mixes in perfectly with its surroundings. The terracotta bricks that adorn the exterior are created from Moroccan soil and manufactured locally. The terrazzo that was used for the floor and facade is made using a combination of local stone and marble. The Marrakech museum has an air conditioning system with temperature and moisture control to ensure that each piece, whether it’s a couture gown from the exhibition room or a rare book from the subterranean archives, is kept in excellent archival condition.

Jewish Museum, Berlin / Studio Libeskind

The Berlin government held an anonymous competition in 1987 to expand the original Jewish Museum, which had opened in 1933. The goal of the initiative was to re-establish a Jewish presence in Berlin following WWII. Among many other globally known architects, Daniel Libeskind was chosen as the winner in 1988; his design was the only one that used a radical, formal architecture as a theoretically expressive instrument to reflect the Jewish existence before, during, and after the Holocaust. The expansion to the Jewish Museum was much more than a competition/commission for Libeskind; it was about re-establishing and protecting a Berlin identity that had been lost during WWII.

Libeskind’s concept was to depict feelings of absence, emptiness, and invisibility — manifestations of Jewish culture’s demise. It was the act of utilising architecture as a vehicle for story and emotion in order to give visitors a sense of the Holocaust’s impact on both Jewish culture and the city of Berlin. A Void slices through the new building’s zigzagging layout, creating a place that epitomizes absence. It’s a straight line whose impenetrability becomes the focal point for organizing displays. Visitors must cross one of the 60 bridges that open onto this vacuum to get from one side of the museum to the other.

The inside is made of reinforced concrete, which emphasizes the empty areas and dead ends where just a sliver of light enters the room. It’s a symbolic gesture by Libeskind to allow visitors to feel what the Jewish people felt throughout WWII, so that even in the darkest periods when you feel you’ll never get out, a ray of hope restores hope.

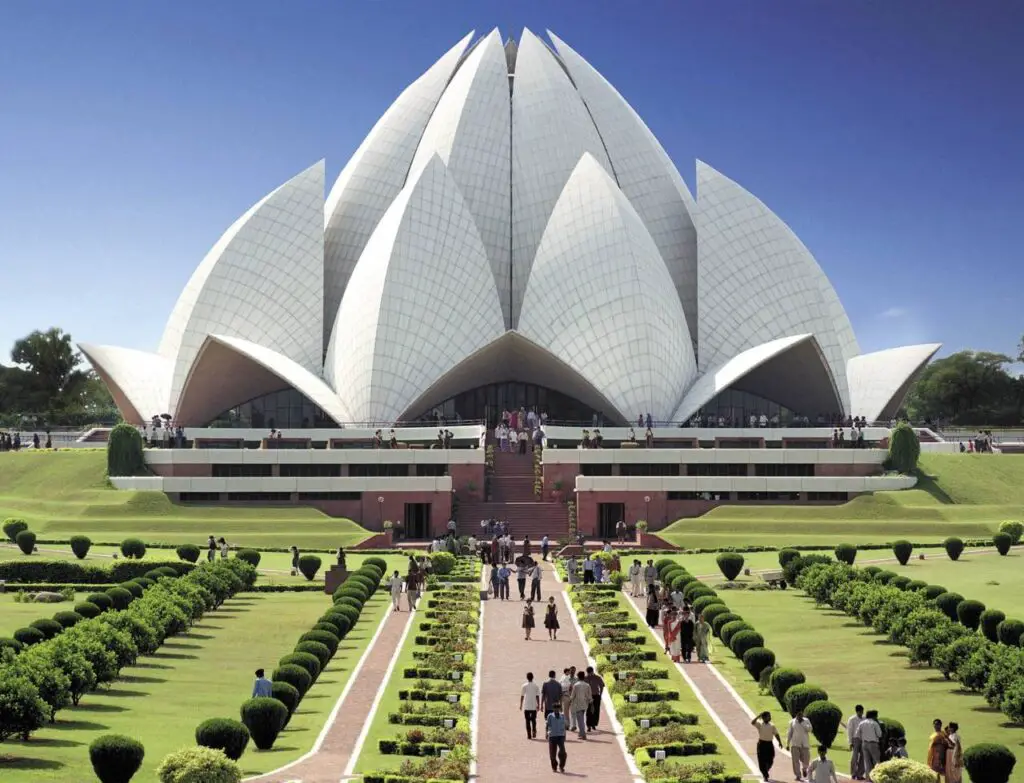

The Lotus temple, New Delhi, India

The temple is one of eight Bahá’ House of Worship facilities across the world, with over 70 million visitors since its completion, making it one of the world’s most visited architectural icons. The Lotus temple is accessible to all practitioners regardless of religious affiliation and serves as a meeting place of devotion for interested guests.

The Lotus Temple and Jorn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House have striking similarities: the Lotus Temple is organized as a nine-sided circular structure with twenty-seven “leaves” (marble-clad free-standing concrete slabs), organized in groups of three on each of the temple’s nine sides, in accordance with Bahá’ scripture.

The aforementioned “leaves” are divided into three categories: entry leaves, outer leaves, and inner leaves, and are essential to the space’s arrangement. The entrance leaves (there are nine in all) mark the entry on each of the complex’s nine sides. The outside leaves provide a canopy for the ancillary chambers, while the inner leaves provide the main worship space. The worship space is crowned with a stunning glass and steel ceiling that approaches but does not meet at the point of the inner leaves.

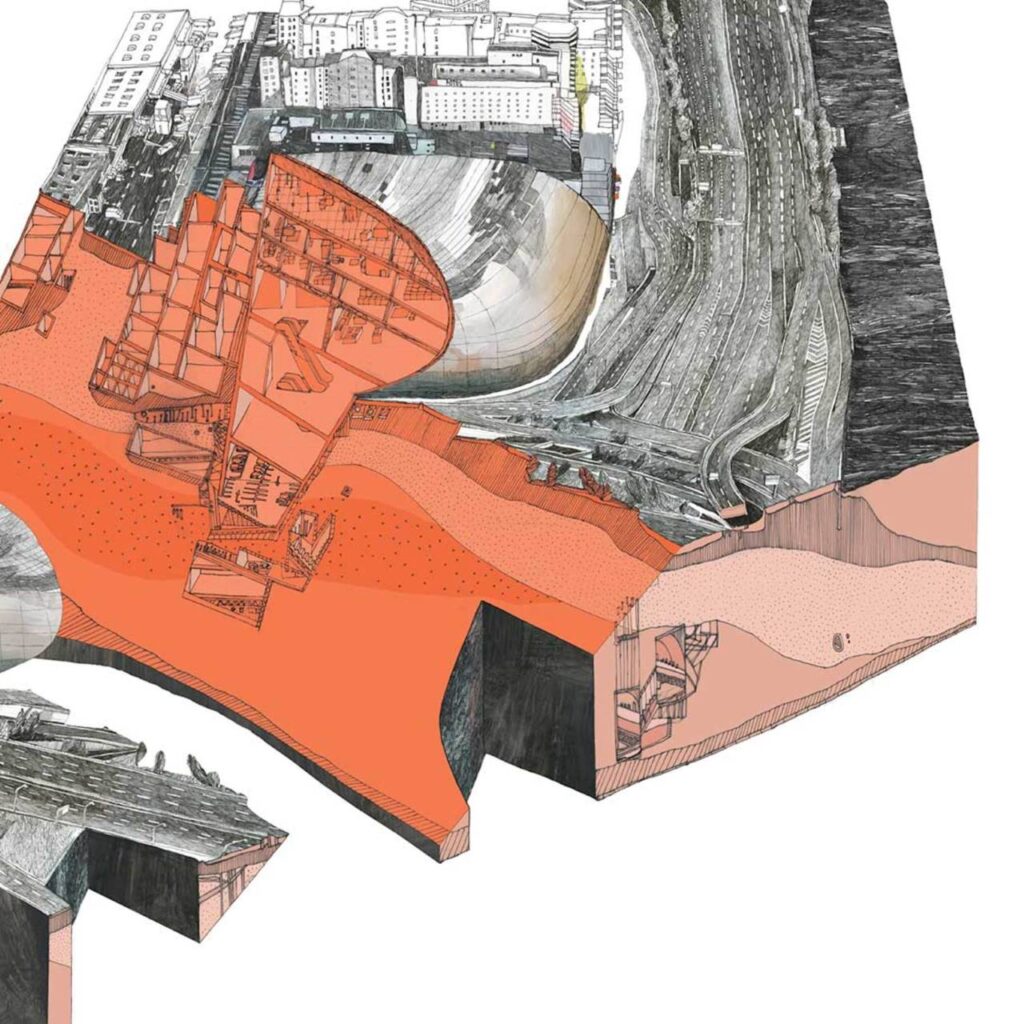

Reconstruction of the fishing village Momonoura via methods of Architectural Ethnography:

A concept already present in the work of the Atelier Bow-Wow, but which became even more apparent when the latter found itself working in the village of Momonoura, in the Miyagi Prefecture, for the reconstruction of a fishing village severely damaged by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami: on that occasion, while gathering testimonies from the local population, it became clear that “rather than urban studies, it was more like we were getting into ethnographic methods.”

As a result, architecture should no longer be viewed just as a means of creation, but rather as a series of activities involving observation, research, and mapping, since, as the curators put it, “life supersedes architecture.”

Hill of the Buddha

The Hill of the Buddha is a Buddhist temple created by Japanese modernist architect Tadao Ando and in Makomanai Takino Cemetery in Sapporo, Japan. The structure was completed in December 2015. The shrine is surrounding by an artificial hill rotunda filled with 150,000 lavender plants and has a 13.5 m (44 ft) tall statue of the Buddha. Only the top of the statue’s head can be seen from outside the hill, which is planted with 150,000 lavenders that allow the environment to vary from green in the spring to purple in the summer to white with snow in the winter.

The design included a pre-existing Buddha statue that had been created in 2000 and stood alone. Only the head of the statue protrudes from the hill when approached, and the shrine is entered.

For an Indian scoop of Architectural Ethnography–

In India, the Kerala Folklore Museum is a one-of-a-kind ethnographic architectural museum. The structure’s three storeys were designed in the different architectural styles of the Malabar, Kochi, and Travancore states. Costumes from ceremonial art forms, musical instruments, traditional jewelry, stone-age implements, masks, and sculptures are among the items in the collection. Thevara is home to the museum.

Open Every day, Time: 9.30 a.m. to 6 p.m., website: www. folkloremuseum.in