What is Sacred Space? Whether man-made or derived from nature, Sacred Space connects us to a reality that transcends fear. A sea, a forest, a rising or setting sun can define “sacred”. But people can create a place to preserve and spread the best within us beyond the world that inevitably threatens and upsets us. Architecture can create places where we feel part of our divine reality.

Creating a space that brings comfort, peace, and a felt spiritual experience while working on functionality is not a simple task for an architect. Buildings specially built for religious activities, whether as churches, temples, chapels, mosques, or synagogues, have been with us for centuries. The heavy power that religion has exerted over the centuries means these buildings are one of the most permanent, expressive, and influential in their respective communities.

On the one hand, a church, mosque, or synagogue does not differ from any other building. It requires the same foundations, fire regulations, and planning considerations as an office building or community center of the same size. But places of worship are far more important in people’s lives than ordinary public buildings, which give the architect an additional responsibility.

Table of Contents

Introduction on Holy places and structures

Architecturally designed modern sacred spaces often avoid traditional religious images, with traditional symbolic elements such as altars and pulpits, and the magnificent and decorated look of the past. Instead, elemental, calm, and unobtrusive spaces, often nodding to natural materials, are gradually becoming the norm. These modern religious buildings are becoming more than just places of worship, they are becoming adaptive and multifunctional spaces that meet the needs of the community.

The ancient architecture of sacred places

If you look at the history of Indian architecture, it’s tempting to classify everything under the broad definition of ‘sacred space’. Indeed, architecture and religion are inextricably linked to Indian architecture. But when we arrive at this, we are amazed at the intrinsic unity of the form and its importance in the ancient architecture of India. Planners in India have offered many interpretations of the sacred space using simple forms, such as circles and squares.

Indian philosophy constantly refers to the concept of “the universe on a grain of sand” in its teachings. Indeed, the very principle of the Antar Atma or inner soul is that it is an all-encompassing soul or microcosm of atman. Ancient architecture in India reflected the concept of indivisibility by using the finite form as a concept representing the intrinsically infinite.

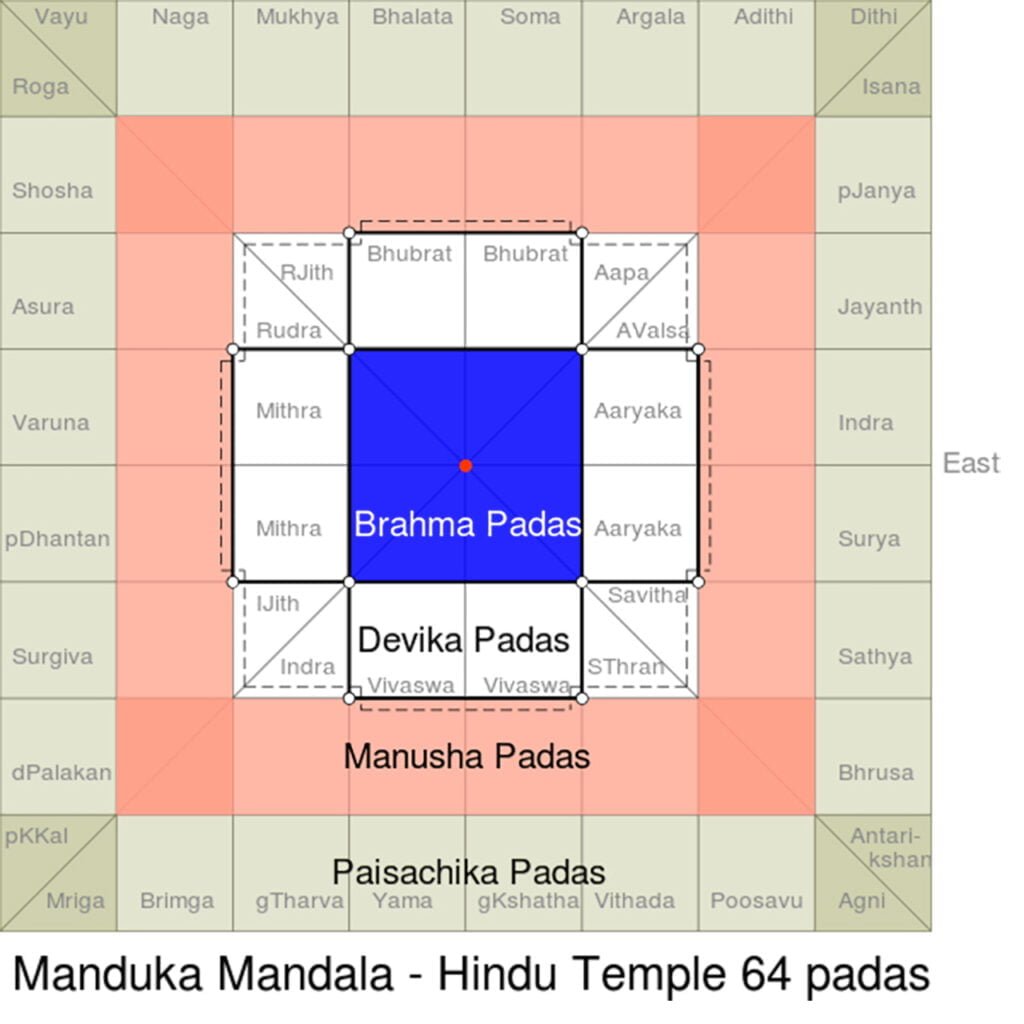

The mandala, or Square

The mandala or square is one of the most basic repeating units in Indian architecture. From the forest-nested Vedic fire altars to the basic orthogonal layouts of the cities of Harapan, to the colossal cathedrals of Khajuraho and Konak, the square and its permutations play an important role in Indian architecture. It is the geometry of a square (which the ancient builders undoubtedly understood) with equal faces and easily calculated diagonals that give this form the concept of constancy.

This square formed the basis of the Vastupurushamandala, or magical plan, on which the temple plans were based. Another square shape, the rectangle, became the basis for many examples of planar forms, such as the Gopuram in South India. Because of their maximum use of space, their static character, and their ease of repetition and combination, the square was one of the most frequently repeated motifs in ancient Indian architecture.

The Circle

Although rarely found as an element of temple planning, the circle was the preferred form in Buddhist architecture, perhaps symbolizing movement and dynamism, and a metaphysical representation of the heavens covering the earth. In the Sanchi stupa and Bharhut stupa, the circle is used in height, as in anda in Sanchi, and Sanchi again in Sanchi and other places. Stone pillars of Ashoka. The dynamic power of the circle is also expressed in more “realistic” applications of Indian temples, such as the “wheel” of the Konark temple in Puri.

The semicircle went one step further to create a perfect circle, giving in to the concept of doubling it or returning its stride from where it was originally. The semicircle used with the metaphysical concept of Pradakshina became a motif in ancient temples, especially the Aihole.

Buddhists also used semicircles on the chaitya to emphasize the stupa’s position at the climax of the chaitya form.

The triangle

The triangle, being the most dynamic of the simple forms, finds a place in ancient Indian architecture, especially in the shikhara of Indian temples, representing the move towards and sympathizing with the divine power in the heavens. Another version of the triangle, although with a rectangular base, is again used in the gopurams of southern India.

The vertical line

Vertical lines are perhaps the most frequent element in ancient Indian architecture, manifesting mainly as decorative columns, in both Buddhist and Hindu architecture. Perhaps realizing the power of the lineage, Ashoka built his pillars to spread his teachings and the message of Buddhism. When repetition is added to this vertical unity, we get a dynamic and virtual facade or division highlighted by columns and walls of columns, for example, in rooms mandapa and interior by Karle chaitya.

The implied space or the void

The implied space or emptiness itself creates very powerful mythological and mystical connotations. Representing the “great unknown”, the restriction of space, or even the number “0”, Indian architecture skillfully uses voids to represent sacred space. The emptiness that can be seen within the confines of the temple – garbha griha – represents the “inner space” of man or antaraatman. Other ways to use the void are in sacred baths – in the grand temple of Modhera, for example.

Buddhists also use emptiness to represent inner space in their viharas and chaitya, and carefully invert the concept into one that is, as at the Sanchi stupa, not a space ” empty” but a filled structure. We may never know how much emptiness may have been realized in Indian architecture, as the largest temple to date – the Konark in Puri – partially collapsed under the weight itself, the rest was blockaded by colonial regimes.

Stonehenge

Many mysteries remain about Stonehenge’s prehistoric sites, but they were sacred sites designed with agricultural concerns in mind. Giant stones (monoliths), each up to 25 tons used in the construction of Stonehenge, were transported from a distance of at least 20 miles and placed in the correct position at a specific angle to calculate both time and time. Stonehenge was designed as a circle of monoliths, with additional monoliths placed on top (triliths) to create a cohesive stone circle.

Inside the circle was a similar design of a horseshoe-shaped monolith that opened to the northeast. A single monolith called Heel Stone is just northeast of the circle. During the summer solstice, stand in a stone horseshoe and head northeast to see the rising sun from Heel Stone. It is unclear what rituals took place during prehistoric times, but today visitors gather to witness the sunrise at the summer solstice. Many bodies have been found in Stonehenge, suggesting that this site was a very important burial site in prehistoric times.

The Parthenon

The Parthenon in ancient Athens, Greece, was built as the temple of Athena, the goddess of war. The Parthenon was built high on a hill overlooking the sea, allowing Athena to monitor the Greeks and protect them from further attacks. The first temple on the premises was wooden and had a wooden statue of Athena. Both burned during the war with the Persian army around 479 BC.

The olive tree, the symbol of Athena, grew from ashes and was considered by the Greeks to be the symbol that Athena wanted to rebuild. Later, the Parthenon and other surrounding Acropolis structures were made of marble. The Parthenon itself is an open rectangular temple with the entrance facing east and loosely oriented towards the base point.

Ise Jingū (Temple/Shrine of Ise)

Ise Jingū in Japan is a place to show respect to nature to those who practice Shinto. The site itself is a complex of 125 shrines built to worship the spirits of nature called gods, the most famous of which is Amaterasu Omikami, the goddess of the sun. Ise Jingu is a complex place comprising many shrines centered on the two main shrines, Naiku and Geku. Goddess Yata no Kagami is one of Japan’s greatest treasures and is at the Naiku Shrine, which represents the sacred support of the royal family. The mirror symbolizes the truth of ancient Japan, and the Yata no Kagami also means wisdom.

Two sections of the same size next to the east and west will be used alternately every 20 years, and the main shrine of the Naiku will be rebuilt. This ritual last took place in 2013. The cypress trees growing in this area are used to build a new shrine next to the old shrine while the old shrine is being demolished. This process means the destruction and regeneration of nature.

When the old shrine is completely demolished, the “heart pillar”, which shows the central location where the next shrine will be built, will be filled and the site will be covered with white rock. The new shrine is built much like the shrine that began its reconstruction ritual in 690 AD. The shrine is 35 feet x 18 feet and has a long south entrance.

Parameters contributing the spiritual feel of the space

Architecture affects human psychology through certain elements, such as color, form, shape, light, space, etc. The built environment has direct and indirect effects on human psychology. It affects our senses, mood, emotions, motivations, judgments, decisions, health, and participation in physical activity and community life.

The scale of the structure

Sacred spaces usually have soaring high ceilings, showing a sense of connection with heaven and God. In the absence of high ceilings, spaces often open outwards towards nature and society. The human scale is best described as the relationship between the body and its environment. The body is nothing more than an undeniable connection between our sensory experience in the physical world and how we perceive it in our minds.

There is a certain relationship between the space we live in and the body that occupies them. From the monumental dome of Jama Masjid in New Delhi to the narrow zigzag landscape of Balanashi, there is a constant connection between our physical and sensory experiences and all the spaces we live in. The grandeur of Indian space has something that makes us feel small and surrounded.

The spontaneous and delicate connection between the majesty of the temple and the intimacy and intimacy of the alleys creates a dynamic relationship between these spaces and the bodies moving within them.

How can we evoke different senses without falling into the hegemony of prioritizing eyesight over all other senses? Immerse your whole body in the surrounding space, feel the texture of the sculptures of the Temple of Shiva, visually grasp the porosity of the stone that made the stairs of the Holy City, and breathe in the air blowing from the Ganges. We are standing on a suspension bridge. The direct contact between our body and the space we are in promotes a connection with our body.

Materials used

In most Islamic architecture, the materials used were stone and brick. Most buildings were related to Zoroastrianism, but the use of stone was also common in building construction. Lime was used in buildings related to Islam. Why can’t we see lime in Christian buildings? Differences in the building materials used in Islamic, Christian, and Zoroastrian religions have revealed some similarities and differences.

Differences that can arise from the original vision of manufacturing mean that the same material is used more often than other types. For example, the building materials of the church were the same as those used for dwellings until the 4th century.

The walls were made of raw brick, and the palm tree roof was covered with a layer of clay. When Christianity became the state religion of Egypt, the church was built of stone with marble columns and a wooden roof, as is now seen in Cairo. However, it cannot be denied that the phenomena of time and space partially affect the properties of the materials used.

As the use of tiles was seen in the construction of mosques, it resulted from the Arab development of communication with other cultures and architecture. The essential and visible point lies in the different properties of the materials used in the selected building.

Colors

Color and its perception cause various conscious and unconscious stimuli in our psychosocial relationships. Despite its existence and its variations, it is ubiquitous. Besides the constructive elements that make up architectural objects, the application of paint to the surface also affects the user’s spatial experience.

Explaining the relationship between colors and the various properties that determine them, or much of the existing research on these theories, is as complex as it is vast. Color can be associated with psychology, symbolism, and even mysticism. Color has different meanings depending on the artistic, historical, or cultural era. The color changes when exposed to light. Among many other features.

Openings and light

Light is often used cleverly by architects to design religious buildings. There, the play of light and shadow evokes a deeper struggle between good and evil. Heaven and Hell. Tadao Ando’s minimalist Church of Light, built in the late 1980s in urban areas of Japan, is a good example of this. Through the intersection of light and solid, Ando says his dual architecture helps to “create a place for individuals, a zone for oneself in society. Glazed features create transparency and show a welcoming, open attitude that many religions promote today.

Importance of open space in sacred surroundings

In the present century, and with very exciting prospects, nature is not seen as a simple aesthetic jewel or a household object. The landscape is explored as a significant contributor to solutions to the most important challenges facing cities and countries – urban forests for air and stormwater quality management, living walls for water quality. Air quality and energy-conserving construction, rooftop farms for food security, and parks as elements of walking programs to tackle obesity and to support active transportation.

Open Space Sacred Place comprises four specific design elements that work together to support the mission of providing a temporary sanctuary, encouraging reflection, providing comfort, and creating peace. These design elements include portals, paths, destinations, and environments, each of which plays an important role in the overall design of the space.

Portal

The first design element you see upon entering an open sacred space is the portal through which visitors pass. It can be an arch, door, trellis, overhanging tree, or other markers. When you pass through the portal, the space of everyday life is transformed into a space of reflection where you can feel the power of nature.

Surround

The environment comprises design elements that define the boundaries of the sacred space. It may comprise a small fence or natural opening in plants, trees, or existing structures. Whatever it is made of, the surrounding interior feels safe and isolated from the stresses and problems of everyday life.

Path

Walking along the path allows the visitor to focus on their thoughts and gain mindfulness for their surroundings. It could be a straight path through the garden, or it could be a maze that takes visitors back and forth, expanding into smaller spaces. The meditative act of walking along the path can ground you to the earth, creating greater holiness and connection with a particular space.

Destination

A destination is an eye-catching feature or endpoint that draws visitors into a space. It can be a beautiful view, a quiet place away from the noise of the city, or a place to relax and experience the charm, awe, and serenity that nature can offer. When combined, these features can empower and transform the people who visit your space, even if it’s temporary.

Is it possible to create a life that goes beyond provenance in the place we designed? Or does the exquisite humanity of architecture make every attempt impossibly peculiar? Architecture connects people directly to our physical world. Whether or not we collude, a spiritual connection arises. Just listen to the music. As Goethe said, architecture may be “frozen music”, but the language of music is sound, fully accepted, and instantly connected to our brains directly. The architecture uses a more indirect way to do the same.

Architects use materials to shape, create space, capture light, manipulate sound, guide movement, and draw attention, but more than that, architecture triggers differently than music.

You can turn the music up or down, or simply set it to “off”. Architecture is often inevitable and exists at all levels we humans do. It is as universal in our perception as the natural environment around us. Unlike religion, architecture is not a ritual, but the essence of what the entire physical world created by humans provides.