Table of Contents

Introduction

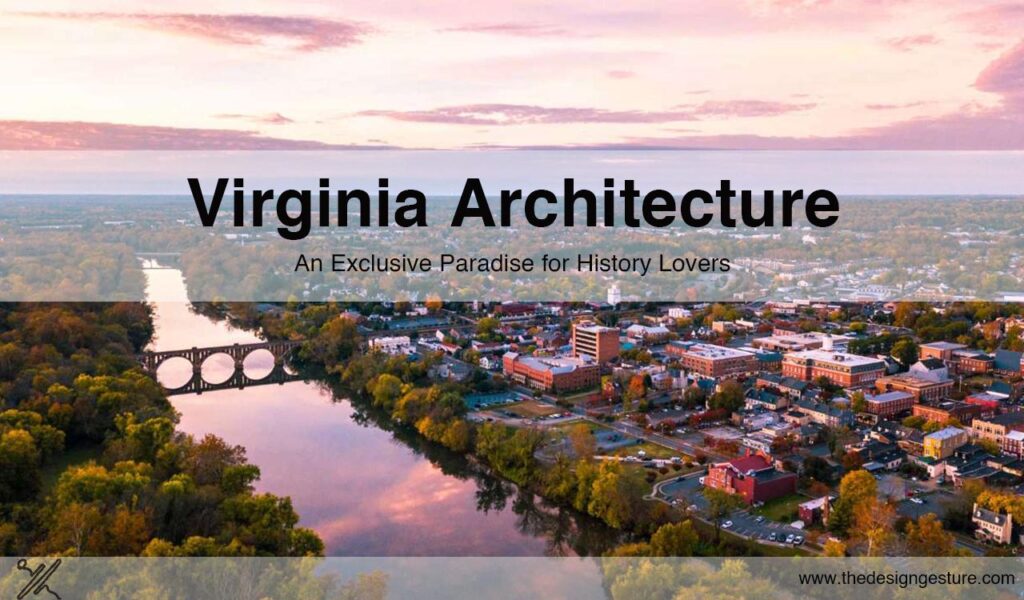

Virginia, a southeastern U.S. state, stretches from the Chesapeake Bay to the Appalachian Mountains, with a long Atlantic coastline. It’s one of the 13 original colonies, with historic landmarks including Monticello, founding father Thomas Jefferson’s iconic Charlottesville plantation. The Jamestown Settlement and Colonial Williamsburg are living-history museums reenacting Colonial and Revolutionary-era life. The area’s history begins with several indigenous groups, including the Powhatan.

In 1607, the London Company established the Colony of Virginia as the first permanent English colony in the New World. Virginia’s state nickname, the Old Dominion, is a reference to this status. Slave labour and land acquired from displaced native tribes fuelled the growing plantation economy, but also fuelled conflicts both inside and outside the colony. Virginia is divided into 95 counties and 38 independent cities, the latter acting in many ways as county-equivalents. The state was split by the American Civil War in 1861 when Virginia’s state government in Richmond joined the Confederacy, but many in the state’s western counties remained loyal to the Union, helping form the state of West Virginia in 1863.

Stunning places to visit in Virginia for Architects

Washington Dulles International Airport

Brief

The civil engineering firm Ammann and Whitney was named lead contractor. The airport was dedicated to President John F. Kennedy and Eisenhower on November 17, 1962. As originally opened, the airport had three long runways and one shorter one. The major terminal was designed in 1958 by famed Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, and it is valued for its graceful beauty, suggestive of flight. In the 1990s, the major terminal at Dulles was reconfigured to allow more space between the front of the building and the ticket counters. Additions at both ends of the major terminal more than doubled the structure’s length.

Design Process/Style

The design included a landscaped man-made lake to collect rainwater, a low-rise hotel, and a row of office buildings along the north side of the main parking lot. The design also included a two-level road in front of the terminal to separate arrival and departure traffic and a federally owned limited access highway connecting the terminal to the Capital Beltway.

Mies van der Rohe house

Brief

3 Chimney House comprises a series of structures that are organised in a Y-shape on a 45-acre property outside of Charlottesville in horse country. The slender, white chimneys reach 30-feet high in the sky, enhancing the home’s varied construction. 2 double-height structures have gables while a low-slung, single-storey volume is topped with a slanting roofline and links to a flat-roofed portion. The firm designed the residence for a young family with deep roots in the region that wanted the house to link with the natural landscape and the area’s historic colonial homes.

Design Process/Style

Unifying the design are brick walls with flush mortar joints painted white and copper roofs that extend down to form exterior walls and which will patinate over time. Upon entering via the single-story structure, called the Main Hall, is a large room with a soaring ceiling. A fireplace divides a sitting area on one side and a shared kitchen and dining area opposite. Interiors are pared-down with white walls and pale wood floors. A variety of window sizes in square and rectangular shapes frame country views and usher in natural light.

National Museum of the United States Army

Brief

Monolithic volumes clad in stainless steel reflect the trees surrounding the National Museum of the United States Army, which architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill has completed in Virginia. The main building is approximately 185,000 square feet and displays selections from the United States Army Center of Military History. Outside this facility is a park with gardens and a parade ground. Stainless steel panels, laser-cut to precisely fit the grid, cover the blocks and reflect the natural surroundings.

Design Process/Style

To add dynamism to the exterior, corners of the blocks feature glass sections and aluminium fins spaced 18 inches apart. Stainless steel pylons matching the cladding are used as stands to showcase individual soldier stories. They are arranged to lead from the exterior promenade, through a glass entrance and into the exhibition hall.

The white coffered ceiling above the lobby, which is also intended to be used as an events space, is decorated with 22 rows of translucent, laminated glass panels coloured to match Army campaign streamers. The ground floor of the three-storey museum comprises shops, a cafe, exhibition spaces, a 300-degree theatre and a terrace. A wide wooden staircase leads from the lobby to the first floor, where additional exhibition spaces are located.

Lynchburg Courthouse

Brief

Home to the Lynchburg Museum, Lynchburg Courthouse was designed by William Ellison and completed in 1855. The courthouse was constructed in the popular Greek Revival style, complete with Doric columns and a portico topped with a pediment. Leading up to the entrance of the courthouse is Monument Terrace, a stair erected as a monument to fallen soldiers from WWI to Vietnam.

Design Process/Style

The building is now home to the Lynchburg Museum, which focuses on the history of Lynchburg and the surrounding area. Gallery themes include history, art and artisans, military history, culture, and the history of the Courthouse itself. The building is capped by a shallow dome located over the intersection of the ridges. At the top of the dome is a small open belfry comprising a circle of small Ionic columns supporting a hemispherical dome.

Monticello

Brief

Monticello was designed and built by founding father Thomas Jefferson from 1770 to 1784, and then remodelled and enlarged from 1796 to 1809. The pinnacle of Jefferson’s Neoclassical Revival style, the home is constructed of red brick with white accents, much like the Academical Village at UVA. There are many uniquely Jeffersonian’s touches throughout, such as disappearing beds, dumbwaiters, and a clock run by weights and pulleys.

Design Process/Style

Work began on what historians would subsequently refer to as “the first Monticello” in 1768, on a plantation of 5,000 acres. Jefferson’s home was built to serve as a plantation house, which ultimately took on the architectural form of a villa. It has many architectural antecedents, but he went beyond them to create something very much his own. He consciously sought to create a new architecture for a new nation. Jefferson added a centre hallway and a parallel set of rooms to the structure, more than doubling its area.

He removed the second full-height story from the original house and replaced it with a mezzanine bedroom floor. The interior is centered on two large rooms, which served as an entrance-hall-museum, where Jefferson displayed his scientific interests, and a music-sitting room. The most dramatic element of the new design was an octagonal dome, which he placed above the west front of the building in place of a second-story portico.

Taubman Museum of Art

Brief

A striking addition to Roanoke’s downtown district, the Randall Stout-designed Taubman Museum of Art is unlike any structure in the city. Inspired by the mountain ridges, gorges and clear streams of the Blue Ridge, the building’s silhouette rises and falls in ridges of glass, steel and zinc. This recent addition to the museum offers 81,000 square feet of gallery, education and public space.

Design Process/Style

Museum staff moved into the Taubman Museum of Art on September 8, 2008. The Taubman Museum of Art opened to the public on November 8, 2008. The permanent collection of over 2,000 works of art includes prominent 19th- and early 20th-century American art, as well as significant modern and contemporary art, photography, design, and decorative arts, and several smaller collections including Southern folk art.

Jefferson Hotel

Brief

A symbol of luxury and style, Richmond’s Jefferson Hotel was built in 1895. Financed by Lewis Ginter, the hotel was designed by Carrere and Hastings, incorporating multiple architectural styles into one magnificent building. The exterior relies mostly on Italian and Spanish Renaissance elements, while much of the interior was destroyed by fire in 1902. Peebles is responsible for the famed Grand Staircase in the east addition, built after the fire.

Design Process/Style

After a fire gutted the interior of the hotel in 1901, it had a lengthy restoration. It reopened in 1907. It has received restorations and upgrades of systems through the years. In the check-in lobby, known as the Palm Court, nine original stained glass Tiffany windows with the hotel’s monogram remain. The three stained glass windows above the front desk and the stained-glass dome are reproductions.

The Academical Village

Brief

Designed by Thomas Jefferson and completed in 1825, the Academical Village serves as the heart of the University of Virginia. The terraced lawn is surrounded by academic and residential buildings, including the University’s most recognizable building, the Rotunda. The Village also houses the preserved dorm room of Edgar Allen Poe, one of the University’s most infamous students. Jefferson’s design has been used as an inspiration for many other green spaces on campuses across the country.

Design Process/Style

The heart of the Academical Village and the University of Virginia’s campus, the Rotunda stands as one of Thomas Jefferson’s most recognizable architectural accomplishments. Modelled after the Pantheon in Rome, the Rotunda was constructed from 1822 to 1826. Ravaged by fire in 1895 and rebuilt with alterations, the Rotunda now stands as Jefferson designed it after being restored from 1973 to 1976.

Thompson Washington DC Hotel

Brief

Thompson Washington DC is an 11-storey hotel by local firm Studios Architecture with interiors by Parts and Labor Design. In the city’s southern Navy Yard neighbourhood, the hotel has 225 guest rooms, an Italian restaurant called Maialino Mare and two rooftop bars. The design draws upon the hotel’s historic industrial site along the Anacostia River, with interiors that are a soft, warm subtle interpretation of its nautical past.

Design Process/Style

The studio designed the hotel with contrasting colours and materials, particularly white surfaces and dark woods. A layering of cream, brown and blue, defines the aesthetic. The design firm custom made most of the furniture and lighting in the Thompson Washington DC hotel. Cream and blue-tone rugs and furniture and sofas in a dusty sea foam colour are used to soften the communal spaces, with accents of yellow and black are interspersed throughout.

Hotel rooms have white walls, floor-to-ceiling windows, soft blue accents, dark wood furniture and hazel oak floors. The guest rooms have a slightly colonial feel whilst also quietly referencing ship cabins. Each suite has a custom, dark-oak headboard upholstered in a wool boucle and leather. Bathrooms have green onyx vanity tops, marble tiled floors, and blue and white tile walls.

Virginia Tech War Memorial Chapel

Brief

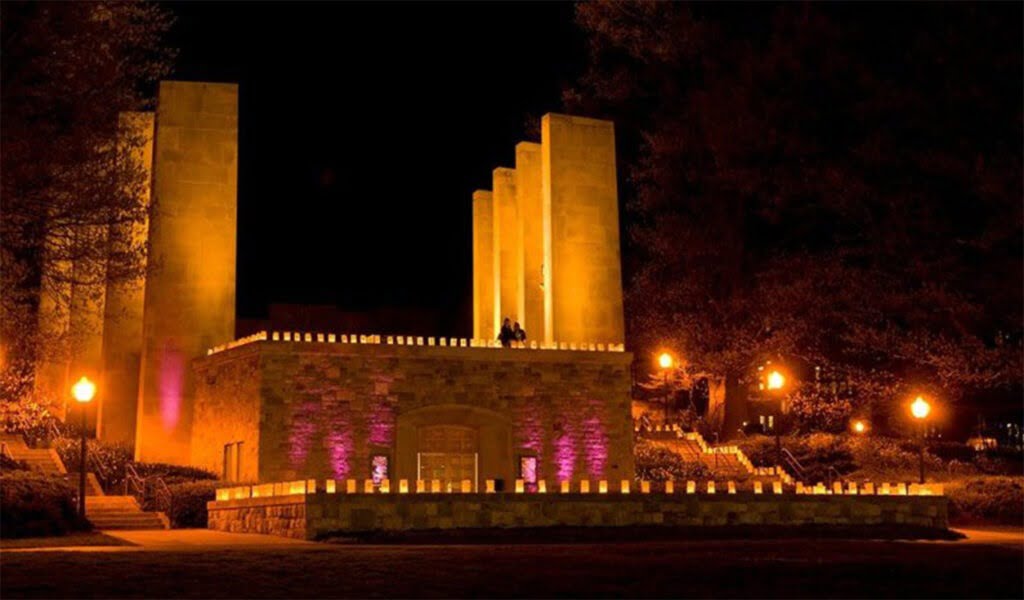

Standing above the War Memorial, the Pylons at Virginia Tech memorialize every student and alumni who died in service from WWI to the present. Each pylon symbolizes one of Virginia Tech’s core values. They stand for Brotherhood, Honor, Leadership, Sacrifice, Service, Loyalty, Duty and Ut Prosim. Overlooking the university’s drill field, the building houses the College of Architecture and Urban Studies.

Design Process/Style

Burruss Hall is constructed of Hokie Stone, a limestone native to the Blacksburg area named after the school’s mascot. Named for Virginia artist P. Buckley Moss, The Moss Center for the Arts is a structure where technology and art exist in harmony. Designed by Norwegian firm Snøhetta, the centre houses classrooms, gallery space, a beautiful 1,280-seat theatre and a “performance laboratory” named the Cube. Opened in 2013, the Moss Center for the Arts is a visually stunning addition to the Virginia Tech campus.

The lower level contains a 6,324-square-foot, 260-seat chapel. A chancel sculpture, designed by Donald DeLue, symbolizes humankind’s relationship to the creator with a central group implying that something greater than humans is responsible for their presence on Earth. The left figure represents this relationship in daily life; the right figure suggests humans in communion with their creator.

Institute of Contemporary Art

Brief

Steven Holl Architects designed the Institute for Contemporary Art to provide the American university with classrooms, galleries and outdoor facilities for its theatre, music and dance programmes. The building comprises a series of irregularly shaped blocks that slot together. Although externally, the building feels like separate volumes, spaces merge inside. The series of volumes are arranged to form two entrances that face both the city and the campus.

Design Process/Style

A pair of irregularly shaped blocks, including one that almost forms a triangle, front the building. Meanwhile, two stacks of rectangular blocks fork open on the campus side, framing a sculpture garden and a pool, described as a Thinking Field. The institute was designed to be a flexible, forward-looking instrument that will both illuminate and serve as a catalyst for the transformative possibilities of contemporary art.

A double-height atrium is wrapped by an organic curving white ceiling. At the centre of the building, it connects three floors of galleries. The fluidity of the design allows for experimentation and will encourage new ways to display and present art that will capitalise on the ingenuity and creativity apparent throughout the VCU campus. The entrance foyer leads through to a cafe bar and shop, as well the ground-floor gallery. Also on this level is a 240-seat auditorium.

A 33-foot-high gallery is set in the apex of the tallest block, along with administrative suites and the boardroom. The building also has a basement floor. Window and skylights are placed to ensure spaces receive plenty of natural light, reducing the need for artificial lighting. Other features include geothermal energy sources that support the heating and cooling systems, and cavity walls designed to keep heat in the winter and provide cooling in the summer.

James River Country House

Brief

The James River House is in the rural town of Scottsville, Virginia, on a hilltop overlooking a river. On a 44-acre forested property, encompassing 2,750 square feet, the home comprises three rectilinear volumes, each serving its own function. The central volume contains public zones, while the wings contain sleeping quarters. The arrangement of these volumes allows the visitor to slip between and through the house, opening the view to reveal light, river and the woods.

Design Process/Style

The team used two different facade strategies. The north side, which looks toward the water, features large windows that provide sweeping views. The volumes were angled away from each other so that residents are afforded several vistas. They then encounter a terrace made of stone pavers and an outdoor fireplace built into the south-facing facade with opaque and angles inward, given its minimal glazing, this side also helps keep the cabin cool during the summer.

Inside, the central volume contains an open-plan kitchen and living room that is both intimate and expansive. A glass-walled walkway connects the main volume to a sleeping wing, which houses the master suite and a children’s bedroom with eight built-in beds. The other volume, which is detached, is dedicated to guests. One of the most important goals of the project was having a minimal impact on the terrain. By elevating portions of the structure, the team could reduce the home’s footprint.