Table of Contents

About

Singapore is a sunny, tropical islet in Southeast Asia, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. Singapore is a megacity, a nation, and a state. It’s about 275 square country miles, lower than the State of Rhode Island, and inhabited by five million people from four major communities; Chinese (maturity), Malay, Indian and Eurasian.

Since its independence on 9 August 1965, the country has espoused an administrative republic system. Presently, the government and the press are led by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong while President Halimah Yacob is the Head of State.

Singapore is known as a City in a Garden and nearly 50 percent of the islet is green space. It’s a thriving megalopolis offering a world-class structure, a completely integrated islet-wide transport network, dynamic business terrain, vibrant living spaces, and a rich culture largely told by the four major communities in Singapore with each offering a different perspective of life in Singapore in terms of culture, religion, food, language, and history.

History

The story of urban planning in Singapore starts from further than 50 years ago. On 12 September 1965, shortly after Singapore had been cast out of the lately formed Malayan confederation and had latterly declared its own independence, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stood before a crowd of city hall sympathizers and said, ‘We made this country from nothing, from mudflats! Ten years from now, this will be a metropolis. Never fear!’

By any mark, this was a bold prediction to make. Granted, 150 times of British social rule had created a thriving entrepôt around the port, a well- waxed civil service, and a rather graphic skyline of neoclassical and art deco piles clustered around the southern tip of the islet. But outside the central business quarter were mudflats and wetlands, and dirt-poor kampong townlets. Utmost of the population lived in squalid, crowded diggings. There was no dependable water force. In real terms, the average Singaporean in 1959 was as poor as the average American in 1860.

Against this sobering background – a megalopolis in a decade? Seemed impossible. But as history shows, Lee’s bold prediction came true.

History of Urban Planning

Urban planning in Singapore aims to optimize the use of the country’s scarce land coffers for the different requirements of both current and unborn generations of the population. It involves allocating land for contending uses similar to casing, commerce, assiduity, premises, transport, recreation, and defense, as well as determining the development viscosity for colorful locales. The way Singapore looks moment is, to a large extent, a result of the government’s effective perpetuation of its civic development plans, the most important of which is the Concept Plan and the Master Plan.

Colonial Town Planning (1819 – 1958)

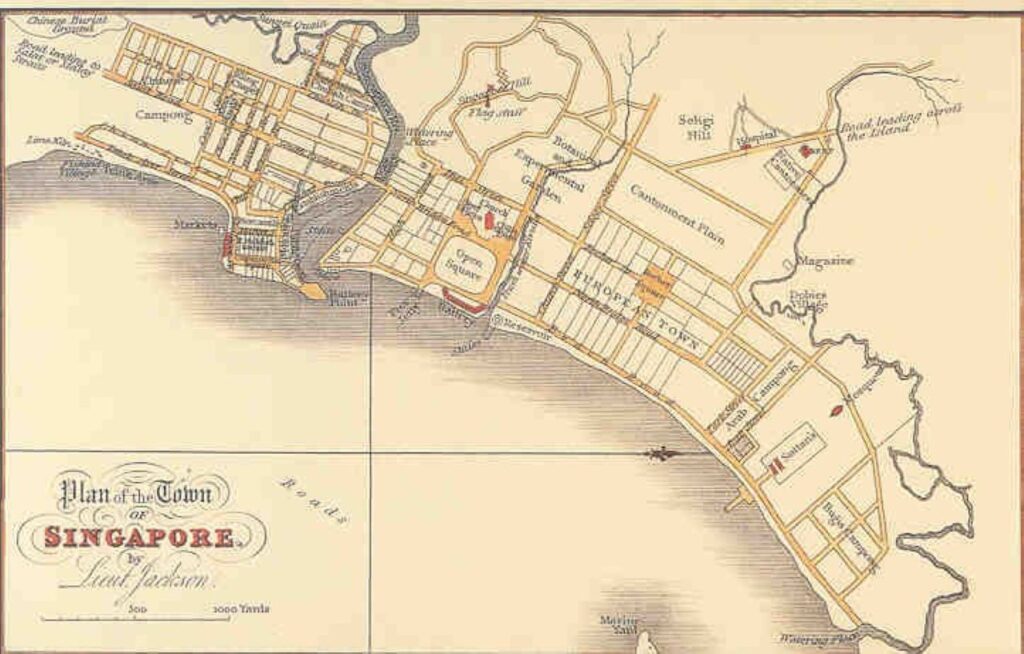

The first urban planning frame in Singapore began in 1822 when Sir Stamford Raffles returned to Singapore and saw the haphazard way the city center had grown. A Town Committee was formed to revise the layout of the agreement. The first detailed megacity plan for Singapore was known as the Jackson Plan, named after Lieutenant Philip Jackson, the agreement’s mastermind and land surveyor in charge of overseeing the islet’s development.

The Jackson Plan guided the growth of the megacity eight times, but the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 brought more vessels and people to the islet, performing in overcrowded, dirty slums, poor hygiene, and sanitation in the megacity area.

In 1927, the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) was set up by the British social government to address the problem of urbanization and ameliorate the physical terrain of the megacity. The SIT worked to widen roads to manage the adding quantum of vehicles, created open spaces, and put in place ultramodern sanitation. Still, it could only make incremental development, as it had no authority to draw up comprehensive plans and control development.

By 1953, the social government realized the dire need for an overall plan to guide the physical growth of Singapore. This redounded in the 1958 statutory Master Plan that regulated land use through zoning, viscosity, and plot rate controls, and reserving lands for colorful amenities. The Planning Constitution, which is now known as the Planning Act, was enforced on 1 February 1960 to lay down the introductory legal frame controlling the use and development of land set out by the Master Plan.

Post-World War II Town Planning (1958 and 1965 Master Plan)

Singapore officially separated from Malaysia on 9 August 1965 and attained independence. As a new nation, the government had a new set of pretensions and precedences of public survival, achievement, making Singapore a global megacity. Survival was important to Singapore because of the communist competitions endured by the new administration in the early 1960s.

Also, the rapid-fire advance in information technology at the time made it essential for Singapore to come to a global megacity. These pretensions, combined with the drive to attain excellence collectively and organizationally as a new country, combine to produce the post-independence planning process.

Unlike the 1958 plan, post-independence planning was forcefully set within the boundaries of main and coastal plans. The need for profitable success was also urgently conveyed in the plans leading up to the 1980s. To this end, planning began to come to an institutionalized, professional act. Moxie was imported to prepare plans, specialist services were attained in the fields of planning, and the State and City Planning (SCP) Department was created.

The original professional staff was transferred overseas to be trained. Post-independence planning was characterized by egalitarian pretensions and icing optimal land use. The land was considered a scarce resource, and allocation of land was a collaborative or public act as opposed to an individual bone. The SCP was concentrated on optimization of the democracy’s land coffers and resolving disagreeing development proffers in the overall interest of the state for the common good.

The 1980s and 1990s

While Singapore’s development concentrated substantially on profitable success during the original post-independence times, as Singaporeans came richer in the 1980s, itineraries started taking into account quality of life factors. Fresh land within new municipalities was allocated for premises and open spaces, while auditoriums and common installations were incorporated into public casing estates to foster a sense of community between resides.

Also, from 1980, artificial planning shifted towards structure and areas suited for advanced value diligence, and artificial areas started to be constructed as” business premises”. These” business premises” had cleaner surroundings than before artificial areas.

The 2000s to present

Public discussion and feedback started playing a lesser part in Singapore’s civic planning from the early 2000s, and for the medication of the 2001 Concept Plan, focus groups were formed to bandy civic planning issues. The 2001 plan substantially concentrated on the quality of life, proposing further different domestic and recreational developments, and balancing the pretensions of liveability and profitable growth.

This included plans to make casing in mature estates, in the new town at Marina South, and at the western area of the islet. Green spaces would be expanded from 2000 to 4500 ha, with the opening of areas similar to Pulau Ubin and the Central Catchment Reserve, which will be accessible by Park Connectors. Sports installations will also be erected for recreational purposes, completing the opening of budgets, where residers can exercise and enjoy near access to nature.

The strategies to sustain a high-quality living environment include:

- Providing good affordable homes with a full range of amenities

- Integrating greenery into the living environment

- Providing greater mobility with enhanced transport connectivity

- Sustaining a vibrant economy with good jobs

- Ensuring room for growth and a good living environment in the future

Urban Systems for Liveability

Sustainable Mobility

The “Lion City” has a character as one of the most strictly planned metropolises in the world. The LTMP 2040 aims for an accessible, presto, and well-connected transport network that can get residents around the megacity in 45 twinkles or less; an inclusive transport ecosystem; and a healthier, cleaner, greener transport terrain. One way they’ve been suitable to achieve and plan for such a cohesive structure is by using the Avoid- Shift- Improve (ASI) frame, a strategy that combines civic transport planning with land-use planning for the long run.

Avoid

The ASI frame aims to achieve GHG emigration reductions, reduced energy consumption, lower traffic, and generally more habitable metropolises. The first step, “avoid,” refers to perfecting the effectiveness of the transport system and reducing the need to travel. In Singapore, homes and businesses are being erected in advanced consistency near to metro stations, so it ’ll take no further than 20 twinkles for residents to travel from home to neighborhood centers.

Shift

The alternate step, “shift,” calls for a shift down from the most energy-consuming modes of transport, like buses, and towards further environmentally friendly modes, like walking, cycling, or public transport. For its part, Singapore has plans to develop a km islet-wide cycle track network by 2040, including a plenitude of places to situate your bike. Singapore’s public transport system is also excellent, and the megacity makes it easy to transfer between its 203 km of metro rail and its near motorcars via its effective chow card system.

Improve

Eventually, the third step, “Improve,” refers to sweats to ameliorate vehicle and energy effectiveness, as well as to optimize public transport structure. Singapore formerly plans to extend its metro rail network with newer and safer technology, as well as add further green motorcars to its being line over the coming decade, making it that much easier to choose public transportation over a passenger vehicle.

But Singapore takes it a step further and actually discourages auto power. The megacity places harsh conditions on both power and the use of particular vehicles. Anyone who wants to buy an auto needs to get a Certificate of Entitlement through a transaction process, which frequently tacks on charges equal to the price of an auto. Likewise, motorists have to pay road druggies charges that vary depending on the time of day.

Singapore is a perfect illustration of a megacity that has effectively combined transport and land-use plans with excellent public transport and disincentives in order to make the ASI frame function. As a result, Singapore has important cleaner air quality than numerous other Asian metropolises, as well as stronger profitable development and increased quality of life.

Sustainable Environment

Singapore has come a long way on its trip towards sustainability. Over 50 times agone, Singapore was dirty and weakened, lacking proper sanitation and facing high severance. It was a small developing islet megacity- state with no natural coffers and faced an uncertain future after its unanticipated separation from Malaysia. Numerous were skeptical that Singapore could indeed survive on its own.

Singapore’s approach to sustainable development is guided by three crucial principles:

- an intertwined approach and long- term strategic planning;

- Investments in R&D and innovative results; and

- forging partnerships.

Through an alliance known as the Singapore Sustainability Alliance, a marquee conforming of government groups, non-governmental associations, and tutoring institutions, Singapore has been suitable to come up with programs that produce a sustainable terrain. Other than this, the alliance has overseen the relinquishment of systems that include proper water use, renewable energy, energy effectiveness, waste operation, etc. which have significantly better business growth.

Conclusion

One of the reasons that Singapore proves to be such a magnet as a home is the ease of living, particularly in terms of hearthstone, transportation, and governance system. Over time, Singapore has made significant strides in numerous areas and has attracted an encouraging number of transnational accolades, which fete the megacity as vibrant and world-class.

So whether it’s the trades and artistic exchanges, the creation of slice- edge invention to enrich the lives of the communities at home or abroad, or the coming together of world-class minds to spark new business openings locally and internationally, Singapore is simply, the place where worlds meet.